Less than seven years are left for Prime Minister Modi’s ambitious Housing for All scheme aimed at providing a home to all the urban poor by 2022. This means an estimated 44,000 homes will have to be built every day or 16 million every year.

IndiaSpend has identified six hurdles that the government must reckon with as it attempts to meet this target:

1. Cities are growing: Two Indian metros, Delhi and Mumbai were among the ten largest urban agglomerations in the world, as on 2014, while another, Kolkata is set to be among the world’s top fifteen by 2030, according to the UN. There were 0.9 million homeless people in urban India as per the Census data of 2011, in addition to a slum population of roughly 65 million. More than 90% of the ensuing housing shortage is constituted by what are called economically-weaker sections and low-income groups, according to government data.

2. A migrant-flood is coming: People from India’s distressed rural areas, home to 833 million people, according to data released by the Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC) survey released earlier this month, are likely to flood into cities and towns in growing numbers as agricultural growth rates flounder. About 670 million people in rural areas live on less than Rs 33 a day, as IndiaSpend reported. India’s urban population is estimated to reach 600 million by 2031, up from about 380 million in 2011. Migrants make up a sizeable chunk of India’s urban population, last estimated at 35 per cent by the National Sample Survey Organisation in 2007-08.

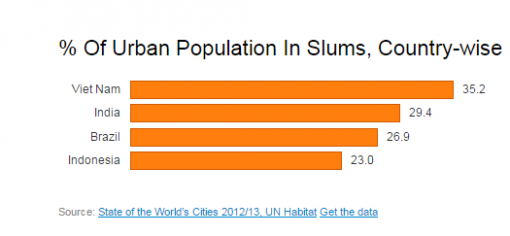

3. Indian slum populations are high: About 17 per cent of urban India–or about 65 million people–today live in slums. While these data are reflected in the Census, on a globally comparable index, the proportion of urban population living in slums in India is high, as the chart below indicates.

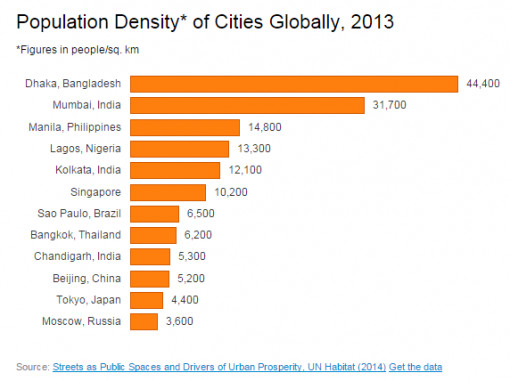

4. Land will be hard to find: An estimated 2 lakh hectares of land will be required to build homes for the poor and plug housing shortages. To deal with the land shortage, some experts have called for vertical expansion by way of floor space index (FSI) relaxations. Mumbai has effected some FSI reform recently. However, most Indian cities are densely populated, with densities running into tens of thousands per square kilometre.

5. Maintaining standards will be a challenge: The sub-components of the Housing-For-All scheme include new units; credit-linked subsidies; beneficiary-led upgradation/construction; and upgrading/redevelopment of slum households. In the rush to build, the quality of construction will be a challenge. As the chart below shows, a third of existing housing units in India are already of a poor standard. This, of course, is not unlike several other emerging economies.

6. Breaking out of the regulatory maze: Among the most difficult challenges of Modi’s housing scheme would be the regulatory maze that enmeshes the construction-approval process in India, which the World Bank ranks as among the worst globally (see chart below). In India the approval process between land acquisition and commencement of construction can take as long as two years, real-estate consultancy Jones Lang LaSalle estimates. ■

| Ease Of Getting Construction Permits Globally |

|---|

| Country | Rank |

|---|

| South Africa | 32 |

| Japan | 83 |

| Bangladesh | 144 |

| Russian Federation | 156 |

| Brazil | 174 |

| China | 179 |

| India | 184 |

Source: Ease of Doing Business, 2014 from World Bank

This article was republished from IndiaSpend.org. Bhunia is a policy consultant.)