Despite significant advances on many economic and social indices, Ahmedabad still falls short on some fronts, according to a new study of the city by the UK think-tank, Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Ahmedabad—India’s fifth most populous—had 6.3 million people in 2011. However, outbreaks of communal violence, such as in 2002, have led to it being called a “shock” city, notes the study, to be released on June 12.

The field-based report, compiled by Indian researchers, finds that the recent top-down approaches to urban issues deliver some results but tends to exclude the urban poor. This is in contrast to the inclusive policies earlier adopted in the city, influenced by Gandhian ideals.

‘Towards a better Life: A cautionary tale of progress in Ahmedabad’ pits the statist approach of Prime Minister Modi – who was Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 – against the previous consensual style of politics.

Since many of Modi’s urban policies were initiated in Ahmedabad, the city may act as a template to examine what can be expected in a country that is witnessing the biggest migration from rural to urban areas in the world. This may include 100 smart cities, his pet project.

The UK study, based on interviews with 50 stakeholders and experts, explores three aspects of this transition:

- material well-being, including income, access to finance and housing

- the environment, with a focus on environmental services and the management of urban expansion

- political voice, through an increase in collective action and stronger local governance

Progress on these indicators, the study notes, has not been even, with many peaks and troughs. What is more, while there have been gains in the city, there have been signs of a recent slowing down and even reversal of progress in poorer households.

Here are key lessons from Ahmedabad, according to the study:

Provide water and sanitation services to slums. Regardless of their legal status, these services are vital steps towards integrating them with the wider urban community.

Most municipal corporations in India are loath to provide this essential service because that it will legalise their tenure. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) has tackled this by disconnecting tenure from the provision of such services.

It issues a no-objection certificate for these services to all the population on the premise that in doing so, the health of the city as a whole can be better ensured. This improves conditions in slum colonies and incorporates them with the larger fabric.

The Slum Networking Project (SNP) was implemented from 1996-2009 collaboratively by the AMC, slum communities and NGOs, which also helped communities to raise funds to upgrade slums. This was the first attempt to extend individual water connections, individual toilets and drainage lines, storm water drains, solid-waste management, street lights and the paving of internal roads.

Resettling slums worsens exclusion. At the same time, the Gujarat government no longer upgrades slums but rehabilitates and resettles these dwellers in colonies set up on the periphery of the city. They have consequently lost their informal jobs since they can’t afford to commute to their earlier places of employment. This has worsened their exclusion.

A major city project which illustrates the top-down approach is the Sabarmati Riverfront Development. The Rs 1,100-crore ($172 million) project, after many delays and cost escalations, reclaimed land on the banks of the river that passes through the city to create parks and promenades.

However, some 14% this land will be sold to real estate developers to cross-subsidise the project, leading to criticism that public land was being privatised. Some 10,000 slum dwellers, squatters on the banks, had to be resettled some distance away.

With gardens on the riverfront—as well as two lakes that have been redeveloped as recreational spaces—with an entry fee, the middle class and developers benefit from ‘development’, Tanvi Bhatkal, a lead author of the study, told IndiaSpend.

Residents formed the Sabarmati Nagarik Adhikar Manch, helped by NGOs. It lodged a PIL in the Gujarat High Court to ensure the government rehabilitated them, the study notes.

Bus rapid-transit system works, but not for the poor. Another project was the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), which has bit the dust in Delhi and Pune but was implemented well in Ahmedabad. Opened in 2009, it now runs for 45 km and is expected to cover 135 km in the next few years.

The state government, displaying the commercial acumen characteristic of Gujaratis, was able to leverage funds under the erstwhile UPA government’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission to roll out these dedicated bus lanes on arterial roads, a low-carbon and people-friendly initiative.

Ahmedabad’s BRTS has received several accolades, including the Sustainable Transport Award from the UN Environment Programme in 2010. However, it has been criticised for being too expensive for the poor and the conventional bus service has been neglected in the process.

Insufficient attention was paid to cyclists and pedestrians along the routes, according to a 2012 study of the system led by Darshini Mahadevia, head of planning at CEPT University in the city, cited by ODI.

The displacement of longstanding markets along the riverbanks and other places prevented street vendors who worked near the riverfront as well as along the BRTS route from making a living, Bhatkal told IndiaSpend.

What sets the Ahmedabad experience apart is how the state portrays projects like the riverfront as inclusive by pointing to the resettlement. It erases the struggles that have gone into ensuring resettlement, Renu Desai of CEPT told IndiaSpend.

Slums, poverty down, industries grow, but low-paid employment. The study lists Ahmedabad’s several achievements. There has been a decline in slum population from 25.6% of the population in 1991 to 4.5% in 2011. Urban poverty also declined, from 28% in 1993-1994 to 10% in 2011-2012 – similar to the national decline from 32% to 14% in cities over the same period.

The city has witnessed the emergence of many industries including petrochemical, refining, pharmaceutical and chemicals, automobile, and agro and food processing enterprises, the study shows.

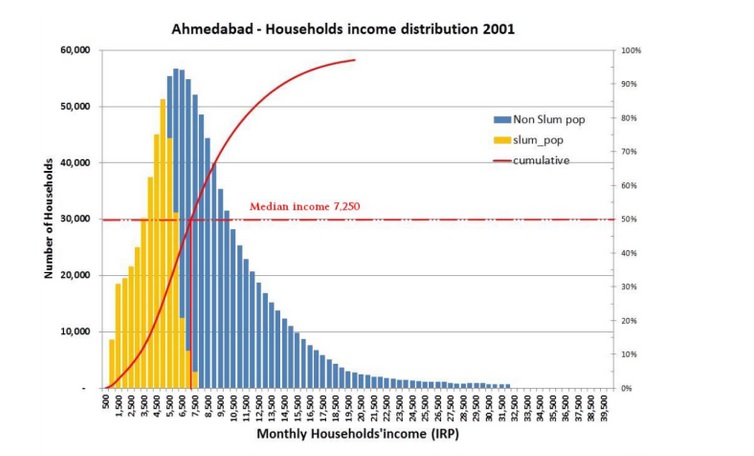

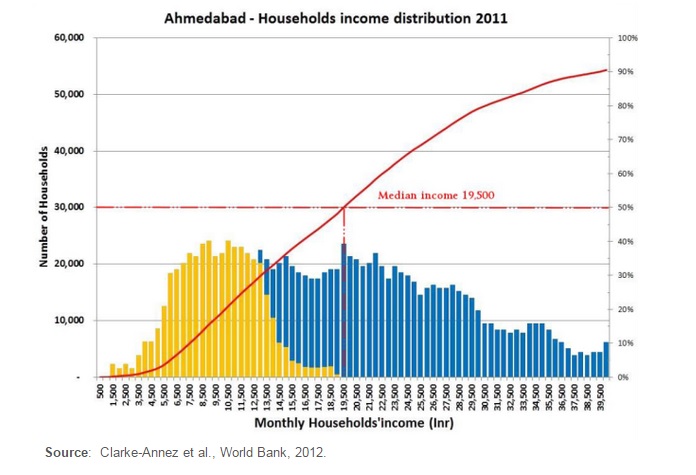

Incomes have increased even among the poor while the median household income increased from Rs 7,500 to Rs 19,500 a month between 2001 and 2011.

However, 80 per cent of the city’s workforce are casual labourers or self-employed.

Some smart growth—controlled by the CM’s office. Ahmedabad demonstrates some characteristics of smart growth through proactive planning for urban expansion. This has helped create a more compact urban area with a much lower sprawl than cities such as Bangalore, Hyderabad and Pune, which have similar populations, says the study.

The AMC has a series of awards: best financial management system (CRISIL National Award, 2003); best practice in city civic centres and e-governance (International Best Practices, 2004); for the Slum Networking Project (UN HABITAT Dubai International Awards, 2006), and Innovative Infrastructure Development (Housing and Urban Development Corporation, 2010).

International researchers who are experts on India refrain from being critical, Mahadevia told IndiaSpend. The AMC has lost its autonomy and is dominated by the CM’s office, she alleged. This is similar to Mumbai, where the CM always holds the urban development portfolio.

The world-renowned Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in the city, led by the Gandhian Ela Bhatt, which the study lauds, has been blacklisted, Mahadevia alleged. Modi distrusted ‘jholawallahs’.

Ahmedabad has not been able to manage its urban sprawl, with new colonies and gated communities coming up on the periphery.

She denied that Ahmedabad was a template for Indian cities because each city was so different.

Madhya Pradesh, irrespective of the party in power, had a relatively better record in pro-welfare policies and exposed the inefficiency of other states’ programmes.

Prosperity up under Modi; progress precedes him. The provision of water and sanitation to the poor—‘watsan’ in planner jargon—preceded Modi in Ahmedabad with the activism of NGOs. Once provided, these were delisted as slums, which accounted for the decline in their numbers.

At the same time, prosperity had increased, leading to better living conditions. Industries like automobiles – including the Tatas’ Nano plant — had sprouted in the periphery. However, there is little trickle-down, with low wages and security.

The study makes no mention of GIFT –

Despite significant advances on many economic and social indices, Ahmedabad still falls short on some fronts, according to a new study of the city by the UK think-tank, Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Ahmedabad—India’s fifth most populous—had 6.3 million people in 2011. However, outbreaks of communal violence, such as in 2002, have led to it being called a “shock” city, notes the study, to be released on June 12.

The field-based report, compiled by Indian researchers, finds that the recent top-down approaches to urban issues deliver some results but tends to exclude the urban poor. This is in contrast to the inclusive policies earlier adopted in the city, influenced by Gandhian ideals.

Towards a better Life: A cautionary tale of progress in Ahmedabad pits the statist approach of Prime Minister Modi – who was Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 – against the previous consensual style of politics.

Since many of Modi’s urban policies were initiated in Ahmedabad, the city may act as a template to examine what can be expected in a country that is witnessing the biggest migration from rural to urban areas in the world. This may include 100 smart cities, his pet project.

The UK study, based on interviews with 50 stakeholders and experts, explores three aspects of this transition:

- material well-being, including income, access to finance and housing

- the environment, with a focus on environmental services and the management of urban expansion

- political voice, through an increase in collective action and stronger local governance

Progress on these indicators, the study notes, has not been even, with many peaks and troughs. What is more, while there have been gains in the city, there have been signs of a recent slowing down and even reversal of progress in poorer households.

Here are key lessons from Ahmedabad, according to the study:

Provide water and sanitation services to slums. Regardless of their legal status, these services are vital steps towards integrating them with the wider urban community.

Most municipal corporations in India are loath to provide this essential service because that it will legalise their tenure. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) has tackled this by disconnecting tenure from the provision of such services.

It issues a no-objection certificate for these services to all the population on the premise that in doing so, the health of the city as a whole can be better ensured. This improves conditions in slum colonies and incorporates them with the larger fabric.

The Slum Networking Project (SNP) was implemented from 1996-2009 collaboratively by the AMC, slum communities and NGOs, which also helped communities to raise funds to upgrade slums. This was the first attempt to extend individual water connections, individual toilets and drainage lines, storm water drains, solid-waste management, street lights and the paving of internal roads.

Resettling slums worsens exclusion. At the same time, the Gujarat government no longer upgrades slums but rehabilitates and resettles these dwellers in colonies set up on the periphery of the city. They have consequently lost their informal jobs since they can’t afford to commute to their earlier places of employment. This has worsened their exclusion.

A major city project which illustrates the top-down approach is the Sabarmati Riverfront Development. The Rs 1,100-crore ($172 million) project, after many delays and cost escalations, reclaimed land on the banks of the river that passes through the city to create parks and promenades.

However, some 14% this land will be sold to real estate developers to cross-subsidise the project, leading to criticism that public land was being privatised. Some 10,000 slum dwellers, squatters on the banks, had to be resettled some distance away.

With gardens on the riverfront—as well as two lakes that have been redeveloped as recreational spaces—with an entry fee, the middle class and developers benefit from ‘development’, Tanvi Bhatkal, a lead author of the study, told IndiaSpend.

Residents formed the Sabarmati Nagarik Adhikar Manch, helped by NGOs. It lodged a PIL in the Gujarat High Court to ensure the government rehabilitated them, the study notes.

Bus rapid-transit system works, but not for the poor. Another project was the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), which has bit the dust in Delhi and Pune but was implemented well in Ahmedabad. Opened in 2009, it now runs for 45 km and is expected to cover 135 km in the next few years.

The state government, displaying the commercial acumen characteristic of Gujaratis, was able to leverage funds under the erstwhile UPA government’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission to roll out these dedicated bus lanes on arterial roads, a low-carbon and people-friendly initiative.

Ahmedabad’s BRTS has received several accolades, including the Sustainable Transport Award from the UN Environment Programme in 2010. However, it has been criticised for being too expensive for the poor and the conventional bus service has been neglected in the process.

Insufficient attention was paid to cyclists and pedestrians along the routes, according to a 2012 study of the system led by Darshini Mahadevia, head of planning at CEPT University in the city, cited by ODI.

The displacement of longstanding markets along the riverbanks and other places prevented street vendors who worked near the riverfront as well as along the BRTS route from making a living, Bhatkal told IndiaSpend.

What sets the Ahmedabad experience apart is how the state portrays projects like the riverfront as inclusive by pointing to the resettlement. It erases the struggles that have gone into ensuring resettlement, Renu Desai of CEPT told IndiaSpend.

Slums, poverty down, industries grow, but low-paid employment. The study lists Ahmedabad’s several achievements. There has been a decline in slum population from 25.6% of the population in 1991 to 4.5% in 2011. Urban poverty also declined, from 28% in 1993-1994 to 10% in 2011-2012 – similar to the national decline from 32% to 14% in cities over the same period.

The city has witnessed the emergence of many industries including petrochemical, refining, pharmaceutical and chemicals, automobile, and agro and food processing enterprises, the study shows.

Incomes have increased even among the poor while the median household income increased from Rs 7,500 to Rs 19,500 a month between 2001 and 2011.

However, 80 per cent of the city’s workforce are casual labourers or self-employed.

Some smart growth—controlled by the CM’s office. Ahmedabad demonstrates some characteristics of smart growth through proactive planning for urban expansion. This has helped create a more compact urban area with a much lower sprawl than cities such as Bangalore, Hyderabad and Pune, which have similar populations, says the study.

The AMC has a series of awards: best financial management system (CRISIL National Award, 2003); best practice in city civic centres and e-governance (International Best Practices, 2004); for the Slum Networking Project (UN HABITAT Dubai International Awards, 2006), and Innovative Infrastructure Development (Housing and Urban Development Corporation, 2010).

International researchers who are experts on India refrain from being critical, Mahadevia told IndiaSpend. The AMC has lost its autonomy and is dominated by the CM’s office, she alleged. This is similar to Mumbai, where the CM always holds the urban development portfolio.

The world-renowned Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in the city, led by the Gandhian Ela Bhatt, which the study lauds, has been blacklisted, Mahadevia alleged. Modi distrusted ‘jholawallahs’.

Ahmedabad has not been able to manage its urban sprawl, with new colonies and gated communities coming up on the periphery.

She denied that Ahmedabad was a template for Indian cities because each city was so different.

Madhya Pradesh, irrespective of the party in power, had a relatively better record in pro-welfare policies and exposed the inefficiency of other states’ programmes.

Prosperity up under Modi; progress precedes him. The provision of water and sanitation to the poor—‘watsan’ in planner jargon—preceded Modi in Ahmedabad with the activism of NGOs. Once provided, these were delisted as slums, which accounted for the decline in their numbers.

At the same time, prosperity had increased, leading to better living conditions. Industries like automobiles – including the Tatas’ Nano plant — had sprouted in the periphery. However, there is little trickle-down, with low wages and security.

The study makes no mention of GIFT – Gujarat International Finance-Tec City, located between Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, which is a “central command and control” Rs 70,000 crore ($11 billion) smart project, Mahadevia observed.

By 2020, it should have up to 7 million people, as much as Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar together today. However, it was unlikely to provide 1 million jobs because Gujarat lacked these skills. States like Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu were more proficient in IT.

Why Ahmedabad? The ODI study was financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It chose Ahmedabad partly because of the Slum Networking Project (SNP) with community participation and also because of land pooling through the town planning schemes.

ODI also separately studied cities in Thailand and Peru. In Thailand, progress on slum upgrading was institutionalised by a nationwide slum upgrading programme, Baan Mankong, which has benefited over 96,000 households. Ahmedabad’s SNP and Baan Mankong are similar in that they involved community mobilisation to contribute to improved housing conditions, said Bhatkal.

The Thai experience has also differed from Ahmedabad. The SNP has a non-eviction guarantee for 10 years in about 60 slums. Initiatives which have achieved greater scale, such as slum electrification and provision of water and sanitation, have delinked tenure from access to services. In contrast, Baan Mankong gives slum dwellers tenure security through collective lease or purchase for the community. ■

D’Monte is Chairperson, Forum of Environmental Journalists of India. This article was republished from IndiaSpend.com.