India has the world’s highest population of stunted children–short for their age–and the country’s failing primary healthcare and overburdened tertiary care are ill-equipped to handle the crisis of childhood malnutrition, leaving India unable to fulfil its national potential.

This is the backdrop against which Finance Minister Arun Jaitley will present his government’s last full budget before the general elections in 2019.

Although India’s stunting rate has declined nearly 10 percentage points in a decade–from 48% in 2005-06 to 38.4% in 2015-16, an estimated 48 million Indian children are still stunted. At a time of declining economic growth and jobs, these children may have a greater disadvantage over those in other emerging nations with lower malnutrition and better healthcare. In addition, Inadequate public healthcare and healthcare expenses push an additional 39 million people back into poverty in India every year, this 2011 Lancet paper said.

Stunting is the percentage of children aged 0-59 months whose height for age is below minus two standard deviations from the median of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Child Growth Standards. It reflects chronic undernutrition. Countries with high rates of stunting are likely to be less prosperous, according to a recent report.

“Until the federal government in India takes health as seriously as many other nations do, India will not fulfil either its national or global potential,” said a November 2017 editorial published in the Lancet, a medical journal.

India spends 1.4% of GDP on health, less than Nepal, Sri Lanka

The Centre’s allocation for health rose 24% to Rs 47,353 crore in 2017-18–from Rs 38,343 crore in 2016-17. This is 1.15% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP). Including the expenditure by states, India spends 1.4% of its GDP on health.

Nepal spends 2.3% of its GDP on health while Sri Lanka spends 2%, data show.

Source: Union Budgets 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18; *Revised estimate, **Budget estimate

The National Health Policy (NHP) envisaged an increase in health expenditure to 2.5% of India’s GDP by 2025.

Without significant increase in its healthcare budget, India’s health targets–reducing its infant mortality rate from 41 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2015-16 to 28 by 2019 and maternal mortality ratio from 167 deaths per 100,000 births in 2013-14 to 100 by 2018-2020, and eliminating tuberculosis by 2025–seem difficult to achieve.

More than seven in ten Indians are not covered by insurance–Indians are the sixth biggest out-of-pocket health spenders in the low-middle income group of 50 nations, as IndiaSpendreported in May 2017. As many as 52.5 million Indians were impoverished due to health costs in 2011–almost half of the world’s impoverished population annually–Factchecker.inreported in December 2017.

India’s 48 mn stunted will grow up to be less healthy and productive

India has the highest population of children stunted (low height for age) due to malnutrition, at 48.2 million.

“Stunting is a proxy for overall cognitive and physical underdevelopment,” according to a September 2017 report published by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “Stunted children will be less healthy and productive for the rest of their lives, and countries with high rates of stunting will be less prosperous.”

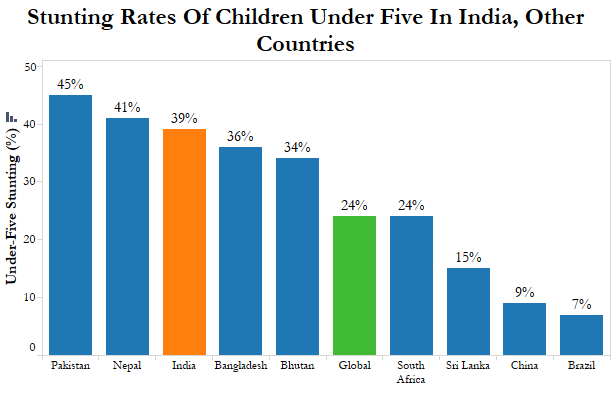

In 2015, nearly two in five Indian children (39%) were stunted–short for their age. In South Asia, only Nepal (41%) and Pakistan (45%) have a larger proportion of stunted children than India, IndiaSpendreported in July 2016.

Source: Global Nutrition Report 2015

Adults who were stunted at age two completed nearly one year less school than non-stunted individuals, according to this study conducted by University of Atlanta in 2010.

Similarly, a study of Guatemalan adults found that those stunted as children had less schooling, lower test performances, lower household per capita expenditure and a greater likelihood of being poor. For women, stunting in early life was associated with a lower age at first birth and more pregnancies and children, according to this 2008 World Bank study.

A 1% loss in adult height due to childhood stunting is associated with a 1.4% loss in economic productivity, according to World Bank estimates. Stunted children earn 20% less as adults compared to non-stunted individuals.

“It is my suggestion to the government of India to work with us on stunting,” Jim Yong Kim, president of World Bank, said on his visit to New Delhi in June 2016. “This is the bottom line: if you walk into the future economy with 40% of your workforce having been stunted as children, you are simply not going to be able to compete.”

In 2017, at least 316 infants died in India’s district hospitals

Infant deaths in district hospitals dominated the headlines in 2017–at least 316 infants died in four states last year. India’s failing healthcare system stacks the odds against a child’s survival even before she is conceived, an IndiaSpendinvestigation in September 2017 showed. Government-run community and primary health centres are dysfunctional, while tertiary care institutes, both private and government-run, are overburdened and mismanaged.

India improved its infant mortality–death of children before the age of one–from 57 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2005-06 to 41 in 2015-16, but is still worse compared to poorer neighbours such as Bangladesh (31) and Nepal (29) and the African countries of Rwanda (31) and Botswana (35).

Despite reducing malnutrition, maternal and childhood malnutrition is the leading cause of disease in India causing 15% of India’s disease burden, IndiaSpendreported in November 2017.

India spends, as we said, 1.4% of its GDP on health.

| Public Health Spending Vs Infant Mortality Of India’s Neighbours & Similar Economies |

|---|

| Country | Public Expenditure on Health, 2014 (As % of GDP) | Infant Mortality Rate, 2016 (Deaths per 1,000 live births) |

| India | 1.4 | 35 |

| Bangladesh | 0.8 | 28 |

| Pakistan | 0.9 | 64 |

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 8 |

| Nepal | 2.3 | 28 |

| Afghanistan | 2.9 | 53 |

| Brazil | 3.8 | 14 |

| Russia | 3.7 | 7 |

| China | 3.1 | 9 |

| South Africa | 4.2 | 34 |

Source: World Bank reports on public expenditure and infant mortality

Primary healthcare failing, tertiary care centres overburdened

In 2016, sub-centres were 20% short of human resources, while primary and community health centres were 22% and 30% short, respectively, according to the 2016 Rural Health Statistics (RHS).

Most functioning rural health facilities in India lack basic infrastructure–29% of sub-centres did not have regular water supply, 26% lacked electricity supply and 11% did not have all-weather roads connecting them, according to the 2016 RHS data.

Primary health centres (PHCs) are supposed to be the first point of contact between the village and a medical officer. Each PHC is manned by a medical officer and 14 paramedical staff, and is supposed to be equipped with an operation theatre, six beds, essential laboratory facilities and a pharmacy.

While 63% of primary health centres did not have an operation theatre and 29% lacked a labour room, community health centres were short of 81.5% specialists–surgeon, gynecologists and pediatricians.

“1.5 lakh Health Sub Centres will be transformed into Health and Wellness Centres,” Jaitley said in his budget speech last year, he didn’t dwell on how the change in the name will improve health services or quality in the sub-centres.

In 2014, 58% Indians in rural areas and 68% in urban areas said they use private facilities for inpatient care, according to the 71st round of the National Sample Survey on health, indicating the declining confidence in India’s public health system.

In 2013, India launched the National Health Mission (NHM)–the country’s largest public health programme–to achieve universal access to healthcare by strengthening health systems, institutes and capabilities.

National Health Mission includes National Rural Health Mission and National Urban Health Mission that work for strengthening rural and urban health system, maternal and child health and communicable and noncommunicable diseases.

The allocation to NHM declined from 57% of the health budget in 2016-17 to 56% in 2017-18–despite an absolute increase from Rs 22,197 crore to Rs 26,690 crore.

Only 68% of the funds demanded by states under NHM were approved by the Centre in 2015-16–the year for which latest actual expenditure estimates were available–according to a 2017 analysis by Accountability Initiative, an Delhi-based public policy research institute. This is excluding the northeast and union territories.

Yet, the beneficiaries of Janani Suraksha Yojana–safe motherhood intervention–were low in many states with the high infant mortality rates.

For instance, in 2015-16, only 61% of mothers in Madhya Pradesh, 54% in Bihar and 66% in Assam had benefited from the JSY programme under NHM, according to Accountability Initiative. Assam, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh had the third, fourth and fifth highest infant mortalities in 2015-16.

With inadequate and ill-equipped primary and secondary care, many Indians turn to the overburdened tertiary care centres, often as the last resort.

The budget for Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana–the Prime Minister’s Health Protection Scheme–increased 103% from Rs 1,953 crore in 2016-17 to Rs 3,975 crore in 2017-18.

The scheme aims to reduce regional inequalities by increasing access to tertiary care facilities by upgrading district hospitals and setting up new All India Institutes of Medical Sciences.

The 2017-18 budget also saw a 155% rise in the allocation for establishing new medical colleges–from Rs 1,293 crore in 2016-17 to Rs 3,300 crore.

While this is in line with the 2015 recommendations of the standing committee on functioning of AIIMS, the committee also noted the tertiary care institutes are facing “mammoth patient load” because they are catering to primary and secondary health needs of patients because of poor primary care.

In 2016, three in five deaths were from lifestyle diseases

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)–such as cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder–were responsible for 61.8% of deaths in India in 2016, up from 37.9% deaths in 1990, as IndiaSpend reported in November 2017.

While the allocation for non-communicable diseases increased 72% from Rs 555 crore to Rs 955 crore, only 57% of funds demanded by states were approved by the Centre, according to Accountability initiative.

“India has a NRHM [national rural health mission] hangover,” said Subhojit Dey, part of the Global Burden of Disease project, and co-chairman of the Cancer Interest Group at Delhi’s Public Health Foundation of India, an advocacy. “Maternal and child health and communicable diseases have been India’s priority until now,” he toldIndiaSpend in September 2017.

Public health infrastructure should be reconfigured to tackle non-communicable diseases, Srinath Reddy, public health expert told IndiaSpend in an interview in January, 2018: “From the perspective of chronic disease management and risk reduction; from providing sporadic care for infectious diseases, continuous care has to be infused in the health system, especially at the primary and secondary level because tertiary care can be still about acute care.”

Mental health still largely ignored

Allocation to the National Programme for Mental Health has been stagnant for the past three years. At Rs 35 crore, the programme received 0.07% of India’s 2017-18 health budget.

This is despite the fact that an estimated 10-20 million Indians (1-2% of the population) suffer from severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and nearly 50 million (5% of population)–almost equal to the population of South Africa–suffer from common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety, as IndiaSpend reported in September 2016.

Despite 15 suicides every hour and 133,623 suicides in 2015, India is short of 66,200 psychiatrists and 269,750 psychiatrist nurses.

“Today, nearly 70% of the meagre mental health spending goes to mental institutions,” Ala Alwan, Assistant Director-General of Non-communicable Diseases and Mental Health at the WHO, told the Quint. “If countries spent more at the primary care level, they would be able to reach more people, and start to address problems early enough to reduce the need for expensive hospital care.”