Amit Vaidya, 37, a PhD in economics, savours each day, as only a two-time cancer survivor can.

He doesn’t want others to suffer as he has, so Vaidya has launched an NGO, Healing Vaidya, to share his insights on health and wellness, especially with cancer patients.

“Unlike survivors who want to run a mile from any mention of the word ‘cancer’, I want a daily reminder of the gift of this second life, and why I refuse to take it for granted,” he said.

It’s been less than a year since Vaidya’s cancer went into remission for the second time, and he knows how lucky he is.

“During the course of my treatment, both the first time and the second time around, I made friends with other cancer fighters,” said Vaidya. “They’re all dead.”

Cancer is the most unpredictable and complex of non-communicable diseases, accounting for 7% of Indian mortality, with numbers steadily rising.

Cancer is inching its way up the rankings of killer diseases in India. Since the turn of the century, cancer has overtaken diarrhoeal diseases and respiratory infections, both communicable diseases, to become the fourth major killer disease, based on WHO data. Cancer is tightening its grip on India. Break down the data, and here’s what emerges:

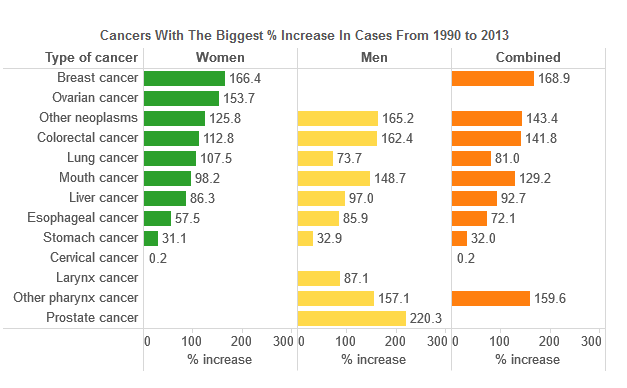

- Between 1990 and 2013, the prevalence of breast cancer increased by 166%, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, an independent global health research organisation at the University of Washington, USA.

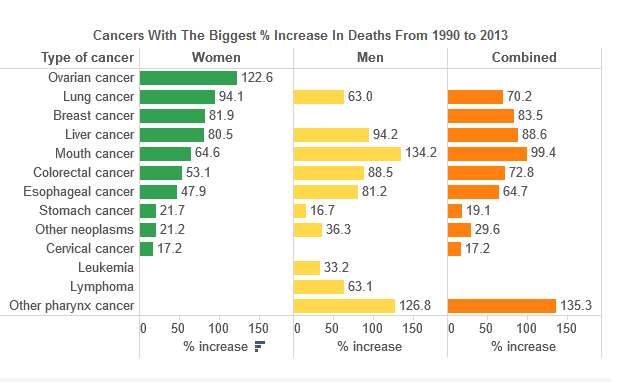

- Over the same period (see table below): prostate cancer cases increased 220%, deaths from ovarian cancer rose 123%, and deaths from mouth cancer among men increased 134%

Source: Global Burden Of Cancer, 2013; View raw data here.

Source: Global Burden Of Cancer, 2013; View raw data here.

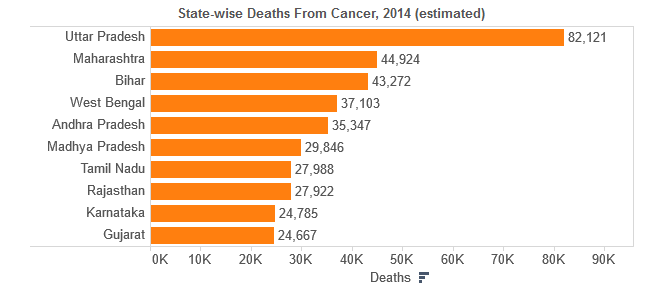

Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, is estimated to have the most cancer cases in 2014. Maharashtra ranks second, followed by Bihar, West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh, according to data released to the Lok Sabha last year.

Source: Lok Sabha

The many faces of the big C

“Cancer is not one disease, but many diseases,” writes oncologist Siddharth Mukherjee, in his Pulitzer-prize winning book, The Emperor of All Maladies—A Biography of Cancer.

Some cancers are caused by lifestyle. Some are caused by pathogens. Some can even be traced to trauma.

However, most cancers in India are caused by lifestyles gone awry.

“Cancer’s unrelenting march in India is being propelled more by flawed lifestyles than by family histories of cancers,” said Mandar Kulkarni, chief technology officer at Cancer Genetics India, a company that offers tests for hard-to-diagnose cancers.

India’s medical fraternity seconds this view.

“I see a clear correlation between less healthy lifestyles and cancer,” said Suresh Advani, medical oncologist, SL Raheja (A Fortis associate) Hospital, Mumbai. “[For example], nine out of 10 of my mouth cancer patients have been consuming tobacco in some form.”

Overall, 45.4% of cancers in men and 16.8% of cancers in women are associated with the use of tobacco, according to the National Cancer Registry Programme’s Consolidated Report of Hospital Based Cancer Registries: 2007-2011.

“While the primary cause for lung cancer is smoking, even second-hand smoke or passive smoking may cause it,” said A K Dewan, medical director & chief of Head & Neck Surgical Oncology, Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute and Research Centre, Delhi.

Other potentially dangerous aberrations of modern lifestyles are late pregnancies, the unhindered use of oral contraceptives, night shifts, and exposure to myriad chemicals through food, personal care products and in the environment–and flawed diets.

India is moving away from wholesome diets rich in fresh fruits and vegetables towards quick-fix meals, processed food and junk food. Processed food is high in fat and low in nutrients.

“People are eating ever increasing quantities of fat, which has eaten into the share of protein we used to consume,” said Advani.

With fat intake soaring and people exercising less, India is packing on pounds. Today, 30 million Indians are obese, which is a risk factor.

Cancer rates in the USA are high and linked with obesity, explained Advani. “India is copying the USA in the way it chooses to eat and live and so, we must be prepared to suffer more from cancer,” he said.

It was while in the USA, in 2004, that Vaidya, 26 at the time, first suffered bouts of vomiting and diarrhoea in quick succession, each time progressively worse. He tested positive for helicobacter pylori, a bacterial infection of the stomach.

“I was told that unchecked helicobacter can cause stomach cancer. After three weeks of antibiotics, I was clear of the bacteria but I was advised to undergo bi-yearly scans for gastric cancer,” he recollected.

Barely two years later, after one such scan, Vaidya learnt that he was suffering from gastric cancer.

Other cancer-causing pathogens are the hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human papilloma virus, transmitted through contact with the body fluids of an infected person.

Chronic stress and depression impairs the immune response, which in turn can initiate and further the progression of cancer—especially in stress-prone personalities.

In 2009, barely a month after Vaidya’s cancer went into remission, his mother was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour.

Mother and son switched roles. The caregiver became a patient and the patient, a caregiver.

The next two years, until she died in 2011, were unbelievably tough. A month later, Vaidya learned just how much recent events had shaken him.

“I got to know that my cancer was back,” he said, “And that it had already metastasised to my liver, lungs and spine.”

Finding the hidden changes that reveal cancer’s slow march

Carcinogenesis—the methodical, step-by-step gene mutations causing the development of early-stage precancerous lesions and their progression into frankly malignant cells—can take decades.

To convey this key message in his book, Mukherjee cites a study from the early 1960s by Oscar Auerbach, a lung pathologist from New Jersey, USA. Auerbach studied lung specimens from 1,522 autopsies of smokers and non-smokers to understand carcinogenesis.

Long before lung cancer grew overtly and symptomatically out of a smoker’s lung, Auerbach found, the lung contained layer upon layer of precancerous lesions in various stages of evolution.

Smoke toxins first caused the outer layer of bronchial airways to thicken and inflame. In these layers, atypical cells with abnormal nuclei developed, then began to show signs of cancer, dividing furiously—evolution gone wild. Only thereafter did clusters of such cells break through the thin lining of basement membranes and manifest themselves as invasive carcinoma. A recent study by Northwestern University in collaboration with Harvard University supports the theory that cancer unfolds slowly. Scientists found blood-cell telomeres, the protective end caps of DNA strands, age much faster in people who develop cancer. This can start as early as 13 years before diagnosis.

Neerja Malik, founder of a support group for cancer patients at Apollo Speciality Hospital, Chennai, underwent a hysterectomy (removal of uterus, ovaries and cervix) in 1995, after suffering major gynaecological issues throughout her married life including “many miscarriages, a stillborn and the nine weeks premature birth of twins”, she said.

“My doctor found precancerous cells in my cervix,” she said. “It is plausible that some changes were going on in my body at that time that eventually led to breast cancer.”

Malik developed breast cancer for the first time in 1998 and for the second time in 2004.

Cancer’s long slow march is a clarion call for taking charge of your life—because, in many cases, the body has the power to heal itself, much like the gradual self-repair of lungs of patients who quit smoking.

An extended lease of life: What you can do

While there is no “silver bullet” for cancer prevention, Rajendra Badwe, director of Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Centre, has a four-point prescription to lower your chances of developing cancer: “Quit tobacco, eat a healthy diet, exercise and maintain personal hygiene.”

Wholesome diets rich in fresh fruits and vegetables offer a range of disease-preventing micro-nutrients, vitamins and trace elements like iodine, iron, etc.

A traditional Indian vegetarian diet rich in spices, such as turmeric, cumin seeds and basil leaves (not chillies), is associated with a reduced risk of oral, oesophageal and breast cancers.

It is also good to stay suspicious, consult a doctor to exclude cancer as a possible disease for health conditions that don’t resolve themselves in a couple of weeks and undergo annual health checks, even if you feel fit.

“Screening can pick up pre-cancerous lesions and early stage cancers of the bladder, kidney, breast, cervix and prostate,” said Mathangi B, physician, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai.

Early detection and treatment improves the odds of survival and of preserving the affected organ.

Cancer survival is usually measured over five to 10 years following diagnosis. “On an average, stage one cases are associated with cure rates of 90%, stage two with 60% and stage three with 30%. The outlook for those presenting in stage four, the last stage, varies,” said Arnab Gupta, surgical oncologist & director, Saroj Gupta Cancer Centre & Research Institute, Thakurpukur, Kolkata.

Awareness about certain cancers, such as breast cancer, has grown, and urban Indians are consulting oncologists earlier, “on an average when they are in stage two or three. It used to be stage three or stage four a decade ago”, said Gupta.

In Western nations, patients typically present themselves in stage one or stage two.

But most patients in India still do not consult a doctor early enough to offer a cure, according to Dewan. Usually, all that can be done for advanced cancers is to provide long-term control or palliation, to use the medical term.

Vaidya knows all about palliation, the uncertainties of cancer and what might work.

At first, his cancer responded to a cocktail of chemotherapy and experimental drugs and radiation, albeit after three years. When the cancer resurfaced in 2011, however, it stubbornly refused to let go its hold on him.

So, armed with palliative-care advice, Vaidya returned to India, ostensibly to say farewell to his family, only to end up at a “cow-therapy” centre in Gujarat. He was prescribed panchgavya treatment—a mix of desi ghee, yoghurt, milk, urine and gobar (cow dung), along with gobar baths, ayurvedic herbs and an organic, vegetarian diet. Vaidya blended in meditation, yoga and elements of naturopathy.

Six weeks on, feeling better, he decided to continue the therapy, living a back-to-basics life in a tiny hamlet in Karnataka for 18 months. Today, he revels in what he calls a “disciplined” life: up at 4:30 am, a satvik diet (rooted in ancient Indian dietary practices), meditation, yoga and running.

That Vaidya’s cancer responded to the cow therapy and simple living does not indicate that it might work for everyone. He is grateful both for the conventional treatment that worked the first time and for the alternative path that, since 2011, has kept him alive. ■

This article is republished from Indiaspend.com