Today, as India announces its voluntary commitments to reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, Indian experts have explained how the country could cut its carbon emissions from short-lived climate pollutants by nearly three-fourths using low-cost methods and, in the process, transform the lives of the poor.

The US, EU and China are among the major countries which have declared their commitments; the global community is waiting to see what India does.

India has already indicated that it is going to take minimalist steps as regards its “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” or INDCs (as they are known in United Nations negotiations), as environment minister Prakash Javadekar said. India will take a further cut on its emissions intensity–the amount of energy used to produce a unit of GDP–from 20-25% on 2005 levels to around 35-40%.

To an extent, current science on climate change justifies this policy, as speakers observed at the sixth annual climate conference, organised by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) in Mumbai, on equity in the forthcoming UN climate summit in Paris this December.

TISS has developed a “carbon budget” for both industrial and developing countries, which provides a clear glimpse of what each is entitled to emit in an equitable framework.

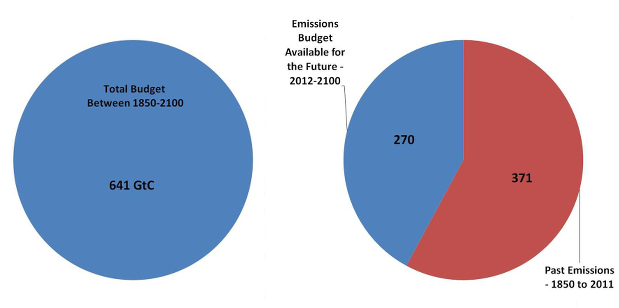

The total amount of emissions from the start of the industrial revolution in 1850 till 2100 is 641 gigatonnes of carbon equivalent (GtC, 1 Gigatonne = 1 billion tonnes), according to Tejal Kanitkar of the Centre for Climate Change at TISS.

If the world’s climate is not to spin out of control when mean temperatures rise by 2⁰C above 1850 levels, there is a total budget of 270 GtC till 2100, as against 371 GtC already emitted from that baseline till 2011.

Source: Tejal Kanitkar, TISS

Developing counties have only “spent” 97 GtC out of the 371 GtC so far.

Industrial countries have only 50 GtC to spend till 2100, while developing nations have 220 GtC left.

However, based on their INDCs made so far before Paris, rich countries will already exceed this budget by 2030 alone.

If the model developed by TISS with the Delhi Science Forum, which takes into account “historical responsibilities” or past emissions, is applied, rich countries can only spend 39 GtC till 2100.

If developing countries leave it to “business as usual” and commits to what “we think is reasonably possible”, Kanitkar says, a 2⁰C rise is inevitable.

But if they cut their emissions steeply, their development plans will go awry, what Kanitkar terms a “lose-lose situation”.

India’s energy options: What greater efficiency could do

While holding industrial countries responsible for putting the world’s climate – and consequently development – back in order, Kanitkar also believes there are tangible, quantifiable trade-offs in undertaking mitigation actions domestically.

“We can’t be cavalier about it – lots of homework is needed,” she says.

This can be taken further by examining India’s energy options. An aggressive pursuit of efficiency can be a win-win situation, according to Ashok Sreenivas of Prayas, a Pune NGO working largely on energy.

The potential value of saving electricity from appliances is Rs 2.50/kWh (per kilowatt hour, a unit of electricity).

Buildings can be better designed. Improvements can be made in industrial processes, vehicle technology and agricultural pumps.

This requires imposition of standards, such as those introduced by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency. There can be incentives and penalties. This will also create a market for energy-efficient processes and products.

Transport accounts for a tenth of India’s GHG emissions. There could be a shift from road to rail across the nation, greater use of public and non-motorized transport in cities and better spatial planning.

These options will not only reduce GHG emissions but also reduce costs, improve mobility (and hence access to education, jobs etc.), reduce imports and, not least, improve air quality.

Renewable energy is relevant to India for reasons beyond reducing carbon emissions, Prayas states. It uses local resources, impacts the local environment and is price-effective in the long-term.

The government has announced aggressive plans – a capacity of 175 GW by 2022, asIndiaSpend previously reported.

India can tweak policies, such as allowing householders who install rooftop photovoltaic (PV) sets to earn revenue for the surplus electricity they provide to the grid. Such tariffs can be telescopic – they rise with every kWh sold to the electric supply undertaking, providing incentives.

This way, high-end consumers on the conventional grid pay for a high cost resource. In this case, there are no batteries required to store PV energy, making it cheaper and environmentally friendly.

How helping the poor could help India

As many as 800 million households have to make do with poor cooking fuels – a form of energy which is even more vital than electricity. This is both domestically polluting and damaging to the climate.

It also has severe health impacts, Prayas points out. As many as 1.5 million people die prematurely due to household air pollution. It causes 25 million disability-adjusted life years or DALYs — a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health or early death.

Women and young children are most affected in rural homes, while housewives and girls fetch most of the fuel.

The suspended particulate matter and soot generated by inefficient chulhas or cook stoves form a controversial meteorological phenomenon known as the Asian Brown Cloud. These also get deposited on the highest reaches of the Himalaya and the black particles on the snow absorb more heat, causing it to melt.

Apart from the switch to more efficient chulhas, there is a clear development case for rapid uptake of clean, modern fuels like liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)), electricity and biogas, Prayas believes.

Control of short-lived climate pollutants like aerosols or black carbon and tropospheric ozone can mitigate the impact of climate change, Chandra Venkataraman and two colleagues from IIT-Bombay point out.

These are not included under the Kyoto Protocol because their mitigation is perceived to yield no reward. However, they can trigger “radiative forcing”, which are changes in the atmosphere due to GHGs, thereby accentuating ocean level rise.

Reduction in these pollutants as well as CO₂ can arrest South Asian sea level rise by 31-50%.

When black carbon increases, it destabilises the atmosphere and can reduce rainfall.

The three IIT authors cite a 2015 study in Nature titled “Soot and short-lived pollutants provide a political opportunity” by two Americans and Veerbhadra Ramanathan from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California at San Diego.

Ramanathan, who addressed an International Federation of Environmental Journalists congress in Delhi before the Copenhagen summit in 2009, is the world’s foremost authority on the Asian Brown Cloud.

The US authors believe that cutting soot and these pollutants will deliver tangible benefits and show Paris that collective action by the world is possible. After December, they believe, the demonstration of such action will bestow credibility on the UN diplomatic process in climate negotiations.

The emission sources by sector for GHGs differ vastly from those of short-lived pollutants in India, according to the IIT-B study. Thermal power stations and heavy industry contribute 65% of the country’s GHGs while homes are responsible for 53% of transient pollutants.

Other sources, which also differ greatly, are transport, agriculture and brick production.

Of the 53% contributed to the pollutants by homes, chulhas are mostly to blame, together with kerosene wick lamps. Burning crop residue accounts for 14%, while diesel and petrol vehicles account for another 13%.

A tractor-mounted machine can cut and lift rice straws, sow wheat into the bare soil and deposit the straw over the sown area as mulch (and help to retain moisture in the soil), the authors state.

This reduces the time to sow wheat without burning the rice-straw residue. However, this technology doesn’t necessarily increase productivity or profits. It calls for regulation to curb residue burning and policy support for technology adoption.

There are technologies to switch to more efficient brick kilns, designing them in zigzag lines, rather than a conventional trench. At present only 2% of the country’s kilns employ this process and this, once again, calls for a policy prescription.

Bricks can also be fashioned from fly ash, waste from coal-fired power stations, without firing them. Only 12% of the nation’s fly ash is currently used for this purpose.

Replacing traditional technologies could make India lean and clean

Short-lived pollutants are generated by diverse sectors, using traditional technologies with low energy-efficiency and high emissions in homes, farms and brick production.

Biomass chulhas, kerosene wick lamps and crop residue burning contribute 65% of these pollutants’ emissions, while diesel vehicles alone add 10% of these emissions, amounting to 3,800 teragrammes of carbon dioxide equivalent or Tg CO2 eq (1Tg=1 million metric tonnes) per year.

Mitigation actions using currently available technologies can mitigate 70% of present-day emissions from all these sectors.

The authors ask whether such domestic actions to curb emissions from short-lived pollutants will qualify under the UN climate negotiations as voluntary “common, but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”.

A survey of 73 households in Raikhel village in the drought-prone Marathwada region of Maharashtra by Anjali Sharma and Tejal Kanitkar of TISS in 2014 found that 90% used only one stove.

Almost a third of the stoves were used to heat water; 35% had no exhaust mechanism, while 40% were located outside the home.

Half the households purchased firewood, given a landscape which is being increasingly deforested. The use of farm waste was low because it was seasonal.

The TISS researchers stressed the benefit of switching to LPG, if homes could afford it. The drudgery of collecting firewood and indoor pollution were important factors which male-headed households didn’t consider.

As speakers at the TISS conference emphasised, while India has to demand greater contributions by industrial countries at Paris, along with funds and technologies for developing countries to mitigate catastrophic climate change, India can voluntarily cut its emissions with such low-cost methods, which are entirely in its enlightened self-interest and vital to its development progress.

This article has been republished from IndiaSpend.com.