All names have been changed to protect identities.

A long queue snakes through most police stations in Kashmir. From young boys, women with children in tow to families, all wait in line to get a chance to make one call.

Alif Umair has been waiting for six hours at a police station in Downtown area. “I am calling an IT firm in Bangalore to let them know that I have accepted the job offer, which I hope I still have. They sent me the letter the eve of the lockdown but with the communication lines down, I couldn’t convey my acceptance.”

Umair says his parents insisted he leave and go to Bangalore and tell them personally. “I don’t want to leave till the situation settles down or at least the phone lines are working again. I am the only child and with no means to speak to them. I will be worried.”

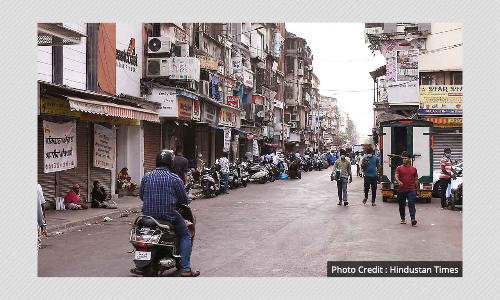

With the communication black-out entering Day 12 on August 16, Kashmiris are losing hope. While the curfew remains in place, many shops raise their shutters post 7.30 pm when the forces withdraw.

“I waited four hours to make a call to my daughter in Delhi the other day. And was allowed to speak to her for only a minute. The policeman kept staring at me till I cut the call,” explains Saira Mir. Mir is 60-years-old and her daughter works at a beauty parlour in Delhi.

“I don’t have the money to go to Delhi and neither does she. This one phone call allotted to us in the only way we reassure each other.”

BOOM spoke to many people at various police stations in the city to understand how the communication blackout is affecting them. At the district commissioner’s office which sees the most number of people queuing up to make international and national phone calls, every third person breaks into tears when speaking to their loved ones.

“I finally spoke to my son in Bangladesh after three days of standing in queues. His wife gave birth to a girl on the night of August 12. We could tell him the news only on August 14,” says Subhan Dar, a daily wage worker in Srinagar. “My son works in a restaurant in Bangladesh. His wife’s delivery date was end of the month but she went into labour early.”

The people who get to make a phone call are lucky ones. The ones who don’t are many. “After standing for hours, I finally got my chance. But my husband’s phone was busy. They didn’t let me try once more,” says Rahath, a young mother of two. “Today I am here again with my children hoping I get to speak to my husband.” Rahath explains that the police officers who have the phones and the DC office employees who monitor treat them like they are doing an illegal activity. “They ask us why I want to make a call, who do I want to speak to, eavesdrop on conversations and sometimes even snatch the phone or keep tutting till we disconnect the call,” she says. “We are all stressed and in pain. Don’t we deserve at least two minutes of a phone call?”

It is not just civilians who are paralysed with no means to reach their family members. Emergency services like ambulances and the fire department are also facing the brunt. An employee of Help Poor Voluntary Trust (HPVT), one of the biggest charitable organisations supplying medicines and ambulances in hospitals says matter-of-factly, “Our priority currently is to transport the deceased back to their homes. The patients have no option but to wait.”

HPVT has at least six to seven ambulances in each government hospital in Srinagar. Currently the only way they are able to cater to people, is when somebody reaches their regional centres and asks them for help. “If an ambulance leaves a hospital, we have no way of knowing when it will return or whether it even reaches safely,” he says.

As a precaution, HPVT has now restricted operations only with a distance of 10-15 kilomteres. “At a hospital, if a patient who has been discharged says he has to go to a distance of 100 kilometres, we have to refuse. That will take too long, sometimes a night with all the curfew in place,” he explains. When asked what happens to those who have to carry the dead body of their loved ones back home, he says, “They get priority. Even if their house is very far, we ensure that an ambulance is assigned to them.”

Many patients who are able to arrange a vehicle for themselves are forgoing the ambulance services. Bilal Mohammed who 85-year-old mother was to be brought to the hospital after severe chest pain refused to take the ambulance stationed near his house. “My brother has a vehicle so we used that. Others in more severe conditions might need the ambulance. We are lucky but others are not,” he said.

BOOM spoke to officials at the Fire and Emergency department services, Kashmir who in hushed tones said, “We have been denied a communication line that people can report crimes on,” said an official. He explained that the department’s seniors had routinely approached the higher-ups for the emergency fire helpline (101) be opened but were met with stiff refusal.

Currently, the department relies on two channels to initiate rescue operations – one the calls coming to the police control room and the second, Running Callers. An officials who keeps a record of all the fire incidents reported explains that the police control room has created a hotline that connects them the fire departments headquarters.

“People reach the nearest police station or the police hears of a fire and then they inform our headquarters.

Once we get the details, we inform the fire station in the area and they mobilise a team,” explained a senior official not wishing to be named. “The rescue ops that would start within 5-10 minutes of receiving a call now take at least 25 minutes because of the many steps that go into sending a fire engine,” he said.

BOOM accessed details of the number of running calls – information of a fire received after somebody ran to the fire station and told them – since the lockdown on August 5.

According to official Fire Department documents seen by BOOM, there have been seven fire incidents reported by running callers in the city of Srinagar.

“The only call we have received via the helpline caused a delay of almost an hour, the longest in our history because the policeman noted the area as Chanapora when the incident had happened in the adjacent neighbourhood – Natipora,” said an official in a frustrated tone.

“Whatever has happened or is happening, at least the emergency services should be functional. Where else do you hear that people run to the fire station to report a fire?”