Studies appear to confirm how poorly India is doing when it comes to creating new technologies and discovering new things, a traditional weakness that, four Nobel laureates said recently, India must address.

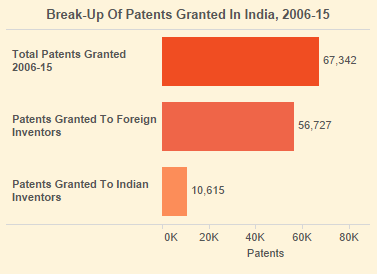

Indian inventors were responsible for only one in six patents granted in the country over the past 10 years, according to an IndiaSpend analysis. The other five patents went to foreign companies looking to protect their intellectual property in the country.

Source: Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks; Note: Data for 2015 up to Dec. 15; View data.

Other studies appear to confirm how poorly India is doing when it comes to creating new technologies and discovering new things, a traditional weakness that, four Nobel laureates said recently, India must address. Before making in India, they said, referring to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s manufacturing plan, companies must invent in India.

“New inventions, technologies, products that can compete on the world stage are in the end based on new discoveries, new understanding of the workings of nature — what we call basic science, which eventually translates into applied sciences and technologies. So my suggestion is that you replace the slogan ‘Make In India’ with the slogan ‘Discover, Invent and Make in India’.— David Gross, Nobel prize laureate for physics, 2004

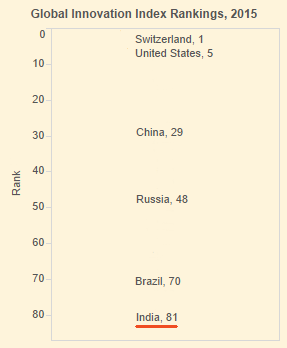

The Global Innovation Index from the World Intellectual Property Organization, a United Nations agency, ranked India 81st of 141 countries in 2015 in innovation.

Source: World Intellectual Property Organization

Government researchers lead the pack; multinationals are strong

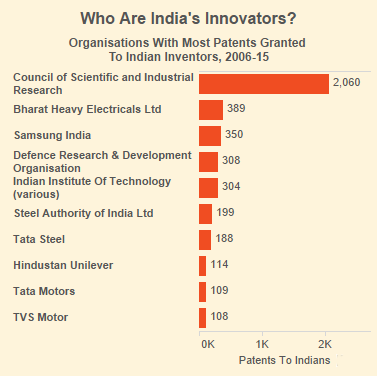

So, India may not be inventing much, but of the little we do come up with, who’s responsible?

The 10,615 patents granted to Indians over the past 10 years, reveal some surprising and not-so-surprising names.

Top of the pack is the premier research and development body in India, the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), with 2,060 patents. The other names are some of India’s biggest public- and private-sector companies.

Source: Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks; Note: Data for 2015 up to Dec. 15; View data.

The strong presence of multinational companies, such as Hindustan Unilever and Samsung, indicate how much research and development they do in India.

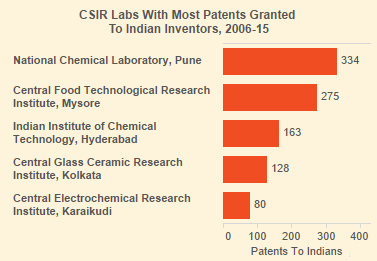

Of CSIR’s 38 labs, the National Chemical Laboratory in Pune, Maharashtra led with 334 patents. If it was a entity separate from CSIR, it could have been India’s fourth-largest innovator.

Source: Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks; Note: Data for 2015 up to Dec. 15; View data.

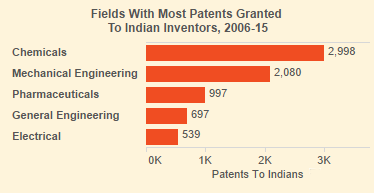

Most patents granted to Indian inventors over the past 10 years were granted for chemicals research.

Source: Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks; Note: Data for 2015 up to Dec. 15; View data.

What is the government doing to further innovation?

The new National Intellectual Property Rights policy could be announced soon.

Going by the draft version, the policy looks to significantly expand the creation and commercialisation of intellectual property.

“We expect [the new policy] to be a visionary document that can guide the journey of India towards becoming an innovative economy in the next 10 years, ” Amitabh Kant, secretary of the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), said last month.

Some measures in the draft version include prodding public-funded research institutions (PFIs) to generate more intellectual property by having it as a “performance metric”, a way to gauge how the institution is doing. Other measures include helping industry and academia interact better.

This is not the first time the government has tried to get PFIs in India, such as the CSIR labs, to invent and patent more.

The Utilisation of Public Funded Intellectual Property Bill introduced in 2009 had similar goals. There was opposition to how the bill made patenting compulsory and how it forced PFIs to provide exclusive licenses on their patents. The argument was that exclusive patents would further monopolies.

A larger ethical issue was that because such institutions get public funding, allowing a private sector company to benefit from their research seemed wrong.

“The bill reinforces the notion that the only appropriate recompense for innovation are intellectual property rights and money…….to sell the idea of commercialisation as a social obligation of a public sector researcher is devious,” Shalini Butani, a New Delhi-based legal activist, argued in a Hindu Business Line column.

The bill was withdrawn in 2014.

In the 12th five-year plan (2012-2017), there is mention of a Patent Acquisition and Collaborative Research & Technology Development (PACE) programme to help Indian companies acquire new technologies from research institutes to further the “Make In India” mission.

PACE would also support the development and demonstration of emerging technologies in these institutes and at multinational companies that involve Indians in research and development.

“If we give confidence to the world on intellectual property rights, we can become a destination globally for their creative work,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi, speaking at an event last April said. But commercialising patents is quite another matter

No more than 5% of patents are successfully commercialised

At an event last month, Kant pointed out how only 5% of all registered innovations were commercialised.

One reason is that much institutional research isn’t applicable to industry and is geared towards getting published in academic journals instead, as this Mint report said.

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, there are many who call the patent system harmful to innovation, especially in information technology.

Vishal Sikka, CEO of Infosys, an information technology company, even called patents “a scourge on the software industry”.

The extent to which patents are seen as a nuisance can be gauged from the opposition to Indian patent office guidelines issued in August 2015. These guidelines allowed patenting of algorithms or software. Such patents would have imposed a cost on other companies in terms of royalties or license fees.

Apart from the additional costs, the accidental use of these methods opens up companies, particularly start-ups, to lawsuits.

“We want Indian entrepreneurs to be focused on innovation and not litigation,” saidVenkatesh Hariharan of software product think-tank iSPIRT to The Economic Times.

Another point is that, given how quickly the software world changes, having patents that are valid for 20 years might not make sense and would only slow innovation. The Indian patent office has now suspended the guidelines.

It’s not just in the software industry that people are rethinking the role of patents. The American electric car maker Tesla has taken the extraordinary step of opening up its patents to others, hoping their use quickens innovation in the electric-car industry.

Given how few companies have gone down this road, it is difficult to say if open patents is an idea whose time has come. ■

This article was republished from IndiaSpend.org. This is the first of a two-part series. Tomorrow: Patent Delays Threaten Make In India.