Medieval charm of Srinagar's Old City

Medieval charm of Srinagar's Old City

Srinagar: Srinagar is one of the oldest cities on the planet, second only to Varanasi, which is today Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s parliamentary constituency. Modern-day Srinagar, in contrast, is the hub of political unrest, and under curfew for over 100 days.

And standing wan sentinels over the unrest in the Valley, in which Srinagar nestles, are the remains of a once beautiful city now in decadence because of government apathy and negligence, said residents of Srinagar.

Mohammad Shafi is one of them. Every morning, the 55-year-old trader commutes seven kilometres from his newly constructed house in Soura Srinagar to throw open his shop in Downtown Srinagar.

The trader, who has lived his entire life in Downtown’s restive Nowhatta locality, had to move to the city’s outskirts after the government ordered the bulldozing of several Downtown residences for road-widening in 2010. In the “outrageous” demolition drive that followed, Old City—“a hub of architectural marvel of the Valley”—lost several heritage structures, forever.

Growing up in bustling lanes of Old City, also known as Shehre-e-Khaas, Shafi and many others put up resistance, but the official order prevailed.

“Ours was a modest house dating back to my grandfather’s time,” said Shafi, sitting in his Nowhatta shop. “We were living happily till the government came up with the road widening plan to disperse Old City’s population which was perceived as a threat to peace.”

In 2010, Old City witnessed intense stone pelting incidents. The protesting youth would often give the slip to the police and paramilitary by disappearing into a maze-like alleyways and lanes.

Late that year, the Omar Abdullah government delivered notice to the residents, asking them to “Be ready to vacate.”

The state government had two Road projects—Syed Merak Shah Road (SMS) and Khanyar-Zadibal-Pandach (KZP)—going. Both the projects passed through Old City.

The two road projects were implemented by the Roads and Buildings (R&B) department at a cost of Rs 336 crore. Officially, 332 residential houses, 750 shops and 145 kanal of land were designated for the two road projects.

The bulldozing that followed did not only decimate physical structures, it also sounded the death knell of the "good old days" spent in those ancestral houses.

“Ours was a lively house located in a lively neighbourhood,” said Shafi. “Every morning, we would see Muslim and Hindu devotees heading for Hari Parbhat for prayers. It was a happening place.”

Not every heritage house in old Srinagar, however, was lost because of the road widening plan. Some were either abandoned or sold in "distress sale" because of security concerns.

Noor Mohammad Chonka, a former resident of Nowhatta, lives these days in the nearby Rainawari locality. He had to sell his house after a neighbour’s residence—Kawoosa House—was allegedly turned into a torture centre in the early 1990s.

“Those days, security forces used to carry three to four search operations a day at my house on the pretext that I was hiding a militant in the house,” said Chonka. “My daughters and my wife felt threatened. Relatives stopped visiting. All these forced me to sell my house to a local trader.”

Those were violent times and Downtown, the heart of the “rebellion”, witnessed a security surge, forcing many well-to-do families to relocate to safer zones. The structures left behind to weather nature’s vagaries were lost to negligence.

Experts, however, said other factors were also at play. They argue that population swell, new housing models and poor government response were also to blame for the calamity that felled these heritage houses.

Saleem Beigh needs no introduction in Srinagar. Mild-mannered, he’s an authority on heritage works. “Government is only focussing on preserving public heritage structures in Old City, including shrines and some historical monuments. It has done nothing for the preservation of old private heritage houses,” said Beigh, coordinator, INTACH.

INTACH, which started functioning in Kashmir in 2002, documented and listed a number of heritage houses and public monuments in 2004.

“We have listed around 4000 structures in old Srinagar,” said Beigh. “Around 900 (of them) are private old houses and (the) rest are public shrines and monuments,” he said.

Beigh said Old City has more heritage properties, both public and private, than at other place in the whole of J&K. “We’ve put a proposal before the government to declare Old City as Heritage City as it has several heritage structures with unique designs,” said Beigh.

Interestingly, the present PDP-BJP government has given an assurance to “rebuild Shehr-e-Khas as a heritage destination by dovetailing craft heritage and tourism”.

Ironically, the J&K Heritage Conservation Act 2010 is yet to be implemented in Kashmir. The Act gives legal status to the houses which need to be preserved.

Many social activists and historians, however, believe it’s the government’s "ill intentions" towards Old City which has led to the destruction of its heritage properties.

“An Old City anywhere in the world is a cradle of culture and tradition, to be preserved and protected. People living in such places should not be displaced as that will lead to an end of the cultural practices,” said Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a poet-historian of Kashmir.

In the 1970s, said Zareef, there was a government plan to widen roads in Old City. “Only those structures were demolished that housed families perceived to be anti-establishment,” said the poet-historian.

“That road widening operation was from Nawa Bazaar to Zaina Kadal, Nowhatta to Gojwara, Rajouri Kadal to Hawal and Khanyar to Nowhatta road. That was a biggest mistake because of which we lost many of our precious and priceless heritage houses.”

Similarly, several heritage houses were decimated in Old City in the 1970s, when the state government drained and filled up the famous water canal, Nallamar.

“That led to the disintegration of several residences on the banks of Nallamar. It was a surgical strike done on its adversaries by the National Conference government,” said Zareef.

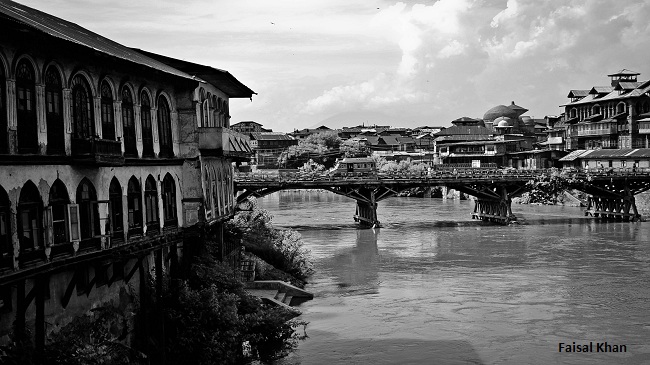

Nallamar - water canal in the Old City of Srinagar

Nallamar - water canal in the Old City of Srinagar

Globally, the concept of Urban Renewal is followed to address population or space issues without disturbing the physicality of the urban space. For example, the Urban Renewal is not to widen roads, but to provide passage to people. It seems, this much-needed concept is still Greek to the town planners of Kashmir.

The result: Weathered and rundown heritage structures in Srinagar’s Old City have taken a hit. Regardless, things weren’t always like this in Downtown. Once the hub of houses of architectural value, nearly six lakh people live in the 2.58 sq km Downtown.

Located on both the sides of the Jhelum—a tributary of the Indus—Old City is built around six bridges. The view from any of the six bridges is unique: Scores and scores of old brick buildings line both the banks of Jhelum. The distinctive pagoda-like roof of a mosque or a shrine enlivens the horizon.

With a maze of narrow and winding streets flanked by two to three-story high buildings, Old City at the level of urban structure is much like other “old parts of town” in the subcontinent.

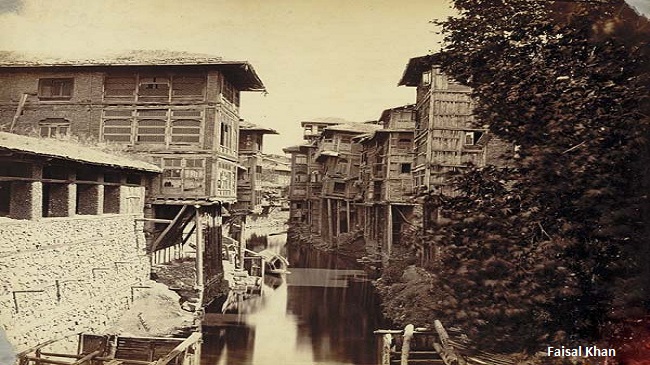

Akin to many other such cities, the existing buildings here seem to be mostly of the late19th to early 20th century era. Observers say there is also an obvious European influence on them. The wooden Pinjra shutters and Maharaji bricks leave many enchanted.

“At present, only 32 designs of windows exist in Kashmir—of them most are in Old City,” said Beigh.

As per the historic accounts, Srinagar was founded by King Pravarasena-II over 2000 years ago. In 631 AD, Chinese traveller Huen Tsang found Old City at the same place where it stands today.

Hindu and the Buddhist kings ruled Srinagar until the 14th century when the Kashmir valley, including Old City, came under the control of several Muslim rulers, including the Mughals.

It was the capital of Yusuf Shah Chak, an Kashmiri ruler, who was tricked into giving up his kingdom to the Mughals by Akbar after the Mughal emperor failed to conquer Kashmir by force. Chak’s remains were buried in Bihar. During Akbar’s rule, Old City got some beautiful mosques and gardens. Much of that medieval charm has faded.

“Two years ago I had to demolish my ancestral house,” said Zahoor Ahmad Waza. “It was too old and my family had grown. I looked for land in Civil Lines but land prices there were exorbitant.”

So, Waza built a five-storey house, the only one that tall in the locality, at the spot where his demolished ancestral house stood, with enough rooms to accommodate everyone in his family.

Ghulam Jeelani Inayati did not take the Waza way out. He continued to live in his 105-year-old family house in Old City even though all his siblings moved to Civil Lines.

“My wife questioned my logic to stay put,” said Inayati. “But when my brothers wished to return, she felt good about my decision.”

Known as Inayati House, it was in this house that the Shahid Kapoor-starrer Haider was partly shot.

“Vishal Baradwaj and his whole team were stunned at seeing the interiors of the house,” said Inayati. “They at once decided to shoot Haider the house.”

Ghulam Ganaie, who is the caretaker of Budshah Tomb—a heritage monument in Old City—said foreign tourists visiting the tomb often insist they be allowed to stay in any of the old houses of Old City.

Traditional houses of the Old City

Traditional houses of the Old City

“They love to stay in these houses,” said Ganaie. “Lots of foreigners flock to Old City. They click pictures of the houses and shrines, reminding us the importance of our houses.”

But In recent years modern architecture has drastically altered the look of Old City. Although the foundations are still laid in the old way—stones for the plinth and wooden panelling—the rest of the structure is in modern style.

Bashir Ahmad Pandit, a local mason, attributes the change to 'outsider-builders'. “Outsiders have greatly altered our architecture,” said Pandit, to the extent they have endangered the lives of Kashmiris.

Srinagar falls in Seismic Zone-V, and the rest of the state in Seismic Zone IV. Experts say traditional houses were built taking into the climate and the seismology of the state. The new houses are not seismic disasters waiting to happen, said locals.

“The old houses were usually built using the Taq system and the Dhajji Diwari,” said Sameer Hamdani, an expert working with INTACH.

Taq system is a bearing wall masonry construction with timber interlacing and Dhajji Diwari is a type of mixed timer and masonry construction.

“Both Taq and Dhajji Diwari employ heavy use of wood, and effectively survive earthquakes because of their flexibility rather than strength,” said Hamdani. “The old houses used to stay cool during summers and warm during winters.”

English author Randolph Langenbach in his book ‘Don’t Tear it Down’ has written “these domiciles” were made keeping in view the earthquakes of Kashmir.

Days before the current unrest in Kashmir, Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti set up a Rs100 crore fund for the re-development of Old City. “Government is identifying some traditional houses for transforming them into libraries and reading rooms,” she said.

INTACH’s Saleem Beigh said INTACH has given a list of heritage houses to the government which were yet to be notified. “Notifying could save the heritage houses from being demolished,” said Beigh.

Admitting that the structures were yet to be notified, Director, Tourism, Farooq Ahmad Shah said it would be done soon. “We have a list of 850 houses which we’re are yet to notify,” Shah said.

“We’ve also introduced a scheme under which Rs 2 lakh will be given to a house owner for renovating his house on the condition that it will also have a paying guest wing,” he said.

These heritage houses aren’t only climate-friendly and earthquake-resistant, they are also unique, said Prof M. Y. Taing of the History Department of the University of Kashmir. “Traditional Kashmiri houses have Central Asian, Iranian, Greek, Chinese and Afghanistan influences,” said Prof Taing.

(Safeena Wani is a Srinagar based independent journalist and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)