Two new toilets were built at a government primary school in Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, but since there’s no outlet, the wastewater stagnates in the toilet.

NEW DELHI: “Ma’am, can I go to the toilet?” asked Sunehra (she uses only one name), a bubbly 12-year-old fifth-standard student of Nigam Pratibha Vidyalaya, a school run by the Municipal Corporation of Delhi in the south-eastern neighbourhood of Sangam Vihar. Since there isn’t a working toilet, she defecates in an open field near the classroom.

“I have used the toilet just two-three times in the school,” Sunehra told Fact Checker. “Even if a few girls use the toilet, it becomes dirty, and we cannot go there anymore. I don’t like to defecate in the open. We are big girls, and many people look at us.”

Sunehra’s concerns represent those of many girls in 45% of Indian schools. They do not have access to a toilet or there are toilets they cannot use and, so, must urinate or defecate in the open in or near schools, according to the 2014 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER). At middle and high schools, there is a correlation between the lack of toilets and drop-out rates, as Mint reported.

On 15th August 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the Swacch Vidyalaya Abhiyan, the Clean Schools Movement, and promised to build separate toilets for 137.7 million boys and girls at schools nationwide within a year.

In this year’s speech he said: “It just came into my heart and I had announced (last year) that we would build separate toilets for boys and girls in all of our schools till the next 15th of August. But later on, when we started work, “Team India” (the government) figured out its responsibilities; we realised that there were 262,000 such schools, where more than 4,25,000 toilets were required to be built. This figure was so big that any government could think about extending the deadline, but it certainly was the resolve of “Team India” that no one should seek any extension. Today, I salute “Team India”, who, keeping the honour of our tricolour National Flag, left no stone unturned to realise that dream, and “Team India” has now nearly achieved the target of building all the toilets”.

[video type='youtube' id='9gDYg0vscHM' height='350']

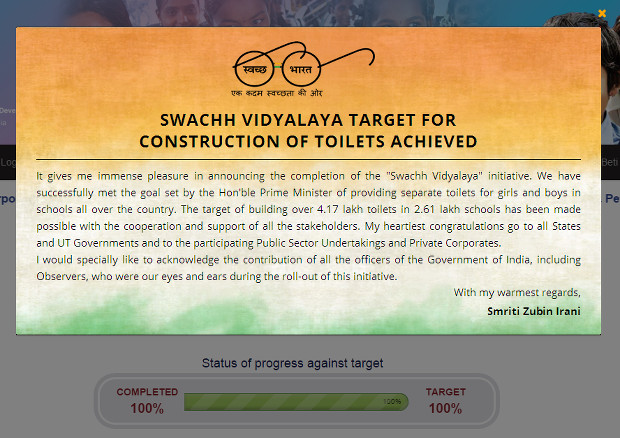

The Ministry of Human Resource Development, the nodal ministry, announced that its targets were achieved, 100%: There were now separate toilets for boys and girls across all schools in India.

Union Minister for Human Resources Development, Smriti Irani, tweeted about it.

| LIST OF APPROVED TOILETS STATE-WISE AND COMPLETED |

|---|

| SERIAL NO. | STATES/UTS | APPROVED | COMPLETED |

|---|

| 1 | Andaman And Nicobar Islands | 71 | 71 |

| 2 | Andhra Pradesh | 49,293 | 49,293 |

| 3 | Arunachal Pradesh | 3,492 | 3,492 |

| 4 | Assam | 35,699 | 35,699 |

| 5 | Bihar | 56,912 | 56,912 |

| 6 | Chhattisgarh | 16,629 | 16,629 |

| 7 | Dadra And Nagar Haveli | 78 | 78 |

| 8 | Daman And Diu | 16 | 16 |

| 9 | Goa | 138 | 138 |

| 10 | Gujarat | 1,521 | 1,521 |

| 11 | Haryana | 1,843 | 1,843 |

| 12 | Himachal Pradesh | 1,175 | 1,175 |

| 13 | Jammu And Kashmir | 16,172 | 16,172 |

| 14 | Jharkhand | 15,795 | 15,795 |

| 15 | Karnataka | 649 | 649 |

| 16 | Kerala | 535 | 535 |

| 17 | Madhya Pradesh | 33,201 | 33,201 |

| 18 | Maharashtra | 5,586 | 5,586 |

| 19 | Manipur | 1,296 | 1,296 |

| 20 | Meghalaya | 8,944 | 8,944 |

| 21 | Mizoram | 1,261 | 1,261 |

| 22 | Nagaland | 666 | 666 |

| 23 | Odisha | 43,501 | 43,501 |

| 24 | Pondicherry | 2 | 2 |

| 25 | Punjab | 1,807 | 1,807 |

| 26 | Rajasthan | 12,083 | 12,083 |

| 27 | Sikkim | 88 | 88 |

| 28 | Tamil Nadu | 7,926 | 7,926 |

| 29 | Telangana | 36,159 | 36,159 |

| 30 | Tripura | 607 | 607 |

| 31 | Uttar Pradesh | 19,626 | 19,626 |

| 32 | Uttarakhand | 2,971 | 2,971 |

| 33 | West Bengal | 42,054 | 42,054 |

| Total | 4,17,796 | 4,17,796 |

Source: Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan

5 reasons the toilet mission appears to have failed

A Fact Checker nationwide check revealed serious problems with the claim that 100% of India’s schools had toilets. If random checks of the kind we did revealed widespread infirmities, it is likely that there are many schools without proper toilets.

Our investigations revealed five larger points:

- The specific claim that every school now has separate toilets for boys and girls in all schools is not true. Many schools that we checked, from urban new Delhi to backward, often remote, areas, such as Chatra district (Jharkhand) and Sedam Taluka, Gulbarga district (Karnataka), do not have toilets.

- Existing toilets in schools in areas such as Delhi, Sitapur (Uttar Pradesh), Tumkur (Karnataka), Dantewada (Chhattisgarh) and Wanaparthy (Telangana)–either already built or new–do not have water or are not maintained. That makes them useless. Without water, they are unusable after a few students use them.

- Newly built toilets in Vidisha (Chief Minister Shivraj Chauhan’s constituency in Madhya Pradesh) , Chatra (Jharkhand) and Baramulla (Jammu & Kashmir) cannot be used because in the rush to build them, they were built without drainage. In Baramulla, a toilet was constructed where there was no school. The school had already been shifted to some other place a year back but still the toilet was constructed to show the work on paper.

- The campaign aimed at constructing 417,000 toilets in 262,000 schools, or 1.5 toilets per school. This means a maximum of two toilets in some schools, one in others. One or two toilets per school is not quite enough (For instance, in Pillangkatta, Ri Bhoi district, Meghalaya, two government schools, each with more than 250 students, have just one toilet each, no separate toilets for boys and girls and no water).

- Educating children in using toilets has proved to be as important as building them. The construction of toilets has been so rushed that various stakeholders do not appear to have had time to understand the importance of the mission and implement it in full measure.

“Well, I cannot comment much, as this is not a political matter,” said Nalin Kohli, BJP spokesperson. “But, if you have some findings, it is good feedback for us. Do share a copy of the findings with me as well.”

Various unsuccessful attempts were made over two weeks to reach minister Irani, HRD secretary Subhash Chandra Khuntia and additional secretary Rina Ray. A copy of our findings has been emailed to all of them.

Upon calling at the Minister’s office, her personal assistant asked for an email. A response received a few hours later said, “Thank you for your email to the Hon’ble Union Minister of Human Resource Development. Your email has been received and will be forwarded to the relevant department for appropriate action.” (This post will be updated if and when we receive a response.)

Many toilets built violate programme requirements

The Clean School campaign’s guidelines specify that there must be separate toilets for boys and girls, with one unit generally having one toilet (western commode or WC) plus three urinals. There should preferably be one toilet for every 40 students.

The guidelines also call for adequate facilities for children with disabilities and for menstruating girls, including soap, private space for changing, adequate water for washing clothes and disposal facilities for menstrual waste, including an incinerator and dust bins.

It is clear that the toilets we saw do not satisfy these guidelines.

The efficiency of local administration plays a big part. In Bhor Taluka, Pune district, toilets in government schools worked well because they had water and were checked and maintained by government officials.

Toilets are, sometimes, central to the decision to attend school. Just six days after the government’s 100% coverage claim, 200 girls from Kasturba Gandhi Awasiya residential school at Ichagarh in Seraikela-Kharswan district, Jharkhand, dropped out because there weren’t enough toilets in school, according to a report in the Times of India. The school had just five toilets for 220 boarders, forcing them into nearby fields, where they were regularly harassed by the local boys.

Even in crowded localities, such as Mango and Jugsalai in East Singhbhum district, Jharkhand, newly built portable toilets in two primary schools (with 40 and 56 students respectively) were unused because there was no disposal pit or water source. While students from Mango were forced to go to the riverside, those from Jugsalai brought their own mugs and water in buckets, according to a report in The Telegraph.

Some part of the toilet-building programme was to be executed by companies under their corporate social responsibility (CSR) obligations. It is unclear how well those plans are working.

Earlier this year, Sunehra’s all-girls school in Delhi’s Sangam Vihar was given some bio-toilets by MAERSK, a shipping multinational, but the bio-toilets are useless. Used by boys during the school’s second shift, they stink, and no one cleans them.

In the context of Fact Checker’s investigation, two questions arise:

- Have the data been manipulated to enable the announcement of “100% completion”?

- Does it make sense to rush construction without ensuring the toilets work?

4,500 toilets per day: Have the data been manipulated?

“As on 3rd August 2015, 3.64 lakh toilets have been constructed. States and Union Territories, public- sector undertakings from 15 central ministries and more than 10 private sector entities are involved in construction of toilets in schools,” said Smriti Irani’s reply to a question in the Rajya Sabha.

This means that 54,000 toilets were built in 12 days at a rate of 4,500 toilets per day, raising questions about the quality of construction.

As many as 22,838 toilets were constructed over seven months between August 2014 and March 2015, (109 toilets per day), while 89,000 were built in 15 days between July 27 and August 11, 2015 (5,933 toilets per day), a rise of 5343%, according to an analysis of the Clean School programme data by Down to Earth magazine.

The report further said that at the end of June 2015, the ministry noted that public-sector undertakings were working very slowly and it appeared that they might not be able to reach the target.

State governments were then asked to take charge of construction projects that had not been finished by public-sector companies and put in an extra effort to reach the target, a fact corroborated by our research.

Another question that arises: How did the government arrive at 417,000, the toilets it wanted to build within a year?

“I find it incredulous a system can suddenly deliver 600% more on sanitation than it has for years,” wrote Nitya Jacob, Head of policy at WaterAid India, an NGO. In a column for the Huffington Post, he argued there were inconsistencies with government data sources.

In 2014, 302,781 primary schools lacked toilets in India, according to the District Information System for Schools (DISE). If schools with defunct toilets are included then, 331,320 schools do not have toilets, which makes the Swacch Vidyalaya numbers a “gross over-estimation”, he said.

The DISE also mentions that 94.24% primary schools have a boys’ toilets, while ASER 2014 puts the figure at 93.7%, wrote Jacob. However, ASER also indicates that in 28.5% of schools, the toilets are unusable—only 65.2% of schools have usable toilets—something the DISE does not mention.

DISE says there are 84.12% usable girls’ toilets, while ASER says there are no more than 55.7%. Using the DISE data exclusively, the number of schools with usable toilets for boys and girls were 944,560 and 806,932 respectively in 2013-14, which meant that to achieve the target of 100%, 504,152 toilets for boys and 641,970 for girls would be needed: A total of 1.14 million new toilets were required, wrote Jacob. Swacch Vidyalaya’s estimation of 417,796 toilets appears to be an underestimation.

Is it enough to build toilets without ensuring that they work?

Sanitation researchers and experts believe that building toilets is not enough. Changing behaviour is equally important.

Sanitation campaigns launched by previous governments–Central Rural Sanitation Program (1986-1999) and Total Sanitation Campaign in 1999 (renamed Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan in 2012)–failed to stop open defecation because they did not emphasise behaviour-change enough.

The progress made this time by central and state governments is significantly more than that made by a previous programme called Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), according to Puneet Shrivastava, manager (policy), Water Aid India, an NGO. But he, too, stressed the need for a behaviour change, alongside the toilet-construction programme.

“There is a need to focus on creating an outcome-focused delivery system where rather than monitoring and measuring outputs/targets for toilet construction, one measures actual usage or, especially in the case of school toilets, functionality and sustainability as well,” said Avani Kapur, Senior Researcher, Accountability Initiative. “However, while the intent is present, unfortunately, somewhere along the way we haven’t been able to build planning, budgeting and monitoring systems that integrate usage as the key indicator.”

In schools, it is “extremely important” to focus on toilet behaviour, said Sudarshana Srinivasan, a former Teach For India fellow who taught at Sunehra’s school in Delhi for two years. “Since children are used to defecating in the open, you cannot expect them to start using toilets overnight,” he said. “We need to teach them to do it, and it takes a lot of time for them to imbibe the practice.”

Experts said government schools in India struggle with larger issues, including absent teachers and corruption. Building toilets and expecting them to be used immediately is unrealistic.

Back in southeast Delhi, Sunehra explained how she wanted to become “something big in life and learn football (her school has had training classes)”. She said: “I want to work hard and fulfil my dream of becoming an airhostess, so that I can earn money and fulfil my parents’ wishes.”

The toilets that the Prime Minister promised are indeed important to her future education and school life. But building them alone is not enough.

This article has been republished from factchecker.in.