What if robots force India to skip a manufacturing-led job growth and go straight to a jobless future?

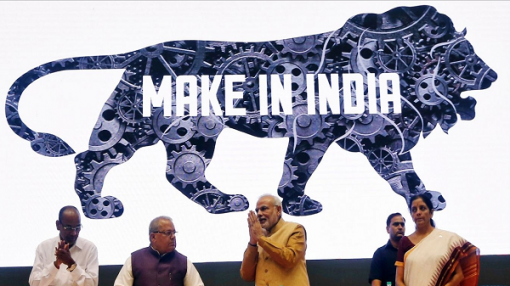

A big part of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) strategy in bringing about “acche din” is the “Make in India” initiative aimed at turning India into a manufacturing hub and providing employment to the youth. But what if these manufacturing jobs are taken away by robots?

Here is an article from The New York Times on robot’s eating away at Chinese manufacturing jobs.

It notes: “Midea, a leading manufacturer of home appliances in the heavily industrialized province of Guangdong, plans to replace 6,000 workers in its residential air-conditioning division, about a fifth of the work force, with automation by the end of the year. Foxconn, which makes consumer electronics for Apple and other companies, plans to automate about 70 percent of factory work within three years, and already has a fully robotic factory in Chengdu. Automation has already had a substantial impact on Chinese factory employment: Between 1995 and 2002 about 16 million factory jobs disappeared, roughly 15 percent of total Chinese manufacturing employment. This trend is poised to accelerate.”

The United States and the western world have already resigned themselves to a future of a robot-driven world where work will dramatically change. There are lists of jobs that robots will take away in the future, how much work will be left over, what will we do once robots have taken away everything and much more information on a robotic world.

India is already feeling the pressure of an increasingly automated world in the IT industry — one of the most prolific job creators over the past two decades. Here is a Chief Information Officer of a large European bank: “When you have the potential to automate certain projects, what difference does it make whether that project is onshore or offshore? It makes that debate irrelevant.”

This is exactly the trend that is creating job pressure on IT majors and reducing employment needs:

“In the traditional outsourcing model, armies of programmers were sent to company sites around the globe. Working in tandem with code writers in India, they focused on stitching together and maintaining systems built around software from global software companies such as SAP and Oracle Corp. The Indian industry is now moving towards having fewer basic code writers but more statisticians and specialist programmers who can create off-the-shelf and branded software.”

Less developed economies have the opportunity to leapfrog intermediate technologies and go straight to the next generation. India skipped landlines and went straight to mobiles. It is also in the process of skipping traditional offline retail and going straight to e-commerce. So, what if robots force the world and India to skip a manufacturing-led job growth and go straight to a jobless future? What happens then?

Experts are confused and divided about the future. One scenario (and this is the optimistic one) has humans moving on to more value-added jobs. After all, when the industrial revolution came in, we all moved on to become typists.

But the more pessimistic scenario is that there may not actually be more high-end jobs to move on to. Here is an article from the Atlantic in “A World Without Work”:

The end-of-work argument has often been dismissed as the “Luddite fallacy,” an allusion to the 19th-century British brutes who smashed textile-making machines at the dawn of the industrial revolution, fearing the machines would put hand-weavers out of work. But some of the most sober economists are beginning to worry that the Luddites weren’t wrong, just premature. When former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers was an MIT undergraduate in the early 1970s, many economists disdained “the stupid people [who] thought that automation was going to make all the jobs go away,” he said at the National Bureau of Economic Research Summer Institute in July 2013. “Until a few years ago, I didn’t think this was a very complicated subject: the Luddites were wrong, and the believers in technology and technological progress were right. I’m not so completely certain now.”

Despite the uncertainty, India’s policy makers may well be advised to embrace the future and prepare for it. Some ideas include expanding welfare programmes to a guaranteed basic income, reducing work weeks so that everybody gets some amount of work and investing in higher end skill and education programmes. India needs to look closely at these and other ideas, and experiment with what works best to prepare for the future.

This article was republished from Newslaundry.com.