Over the past decade, India has been near the bottom of the global rankings, as far as female participation in the urban workforce is concerned. The good news: our analysis of data from the past two decades shows that this is beginning to change. Women (especially young women) are entering and looking to enter the urban workforce in large numbers.

The bad news: unfortunately, most women are only able to find marginal work in the informal economy, with low wages and little or no job security. In addition, highly educated young urban women appear to have very limited job options in urban India.

The growth in the urban female workforce is characterised by two trends—more than 60% of urban females are a part of the informal sector while unemployment is the highest among urban females with graduate degrees and above, with an unemployment rate of 15.7%, much higher than other demographic groups.

India’s urban female work-force participation rate (WPR) is one of the world’s lowest at 15%, ranking eleventh from the bottom among 131 countries, according to a 2012 report on global employment trends by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). This, however, might be changing, with the participation rate growing 5.6% annually since 1991, in comparison with 2% for rural females and 3% for urban males.

Change in labour force participation: the female demographic dividend

Compared to other countries which are at similar levels of development, Indian women tend not to participate as much in wage employment. The WPR for women above 15 years of age in India was a little below 30% in 2011, significantly below the world average of around 50%, according to World Bank estimates. In comparison, Brazil and China were at 60% and 67% for the same age group.

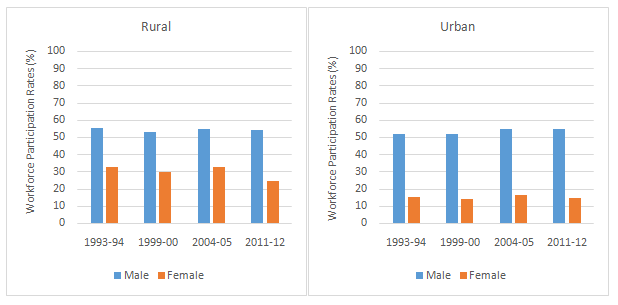

The female WPR is especially low in urban areas and has remained close to 15% over two decades, as Figure 1 shows. Meanwhile, the female WPR in rural areas has varied between 25% and 30% in the same time period. In contrast, urban male participation rate is 53%, according to 2011 National Sample Survey Organisation data (NSSO).

Fig 1: Workforce Participation (UPSS) by Gender and Place of Residence

Source: Employment and Unemployment Survey, NSSO (various rounds)

While several recent studies have highlighted low female WPRs in urban India, we present evidence to show that urban women are beginning to enter the labour market in greater numbers.

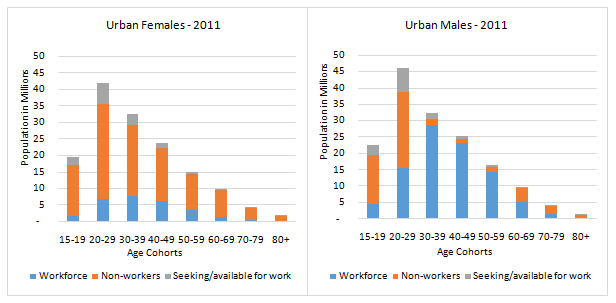

The number of women working and seeking work grew by 14.4% annually between 1991 and 2011, even though the population of urban women grew at only 4.5% during the same time period, according to Census 2011.

The total number of women in the work force increased more than three-fold, from 9 million in 1991 to 28 million in 2011, while the number of women seeking or available for workincreased more than eight-fold, from 1.8 million in 1991 to 15.5 million in 2011.

This means that the number of women in the workforce in 2011 would have been higher by more than 55% if these 15.5 million women were able to find jobs.

In comparison, the male workforce would have increased by only 13% if the 14 million men seeking or available for work found employment. This indicates a significant shift in women’s participation in the labour market in urban areas since 1991.

Fig. 2: Composition of Urban Male and Female Population, 2011

Source: Census of India, 2011

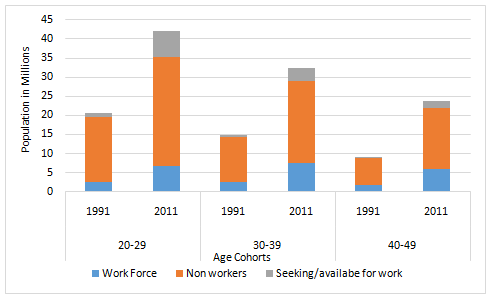

Fig. 3: Urban Female Population Composition 1991 and 2011, Age Group 20-40 years

Source: Census of India, 2011

This fact is corroborated by the Employment and Unemployment Survey 2011 conducted by the NSSO which shows that urban females between 15 and 59 years have the highest unemployment rate at 15.7% as compared to 9% for males belonging to the same age group.

These numbers indicate that urban women are increasingly looking to enter wage employment but are currently unable to find adequate and relevant opportunities.

If this trend continues, women might choose to drop out of the labour force altogether or settle for jobs that are not commensurate with their skills and expectations.

Unemployment is highest for women with graduate degrees and above

At 13.9%, the unemployment rate is highest for urban women with graduate degrees and above. Within this category of educational attainment, the unemployment rate for women aged 15 to 29 is even higher, at 23.4%. This highlights the severity of the problem for educated young women in urban India.

Some studies have suggested that a possible explanation for women voluntarily dropping out of the labour force is the stigma associated with working in jobs that require lesser qualifications.

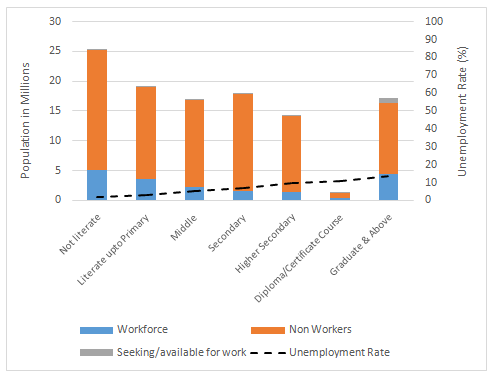

Figure 4 shows the urban female workforce disaggregated by level of educational attainment. The ‘illiterate’ and ‘graduate’ categories have the highest number of workers.

Fig. 4: Work Status of Urban Women by Education Levels, 2011-12

Source: Employment and Unemployment Survey, NSSO 2011-12

The dotted line in Figure 4 shows unemployment rates for women aged 15 and above across categories of educational attainment.

The evidence shows that educated urban women are increasingly seeking work but are unable to find opportunities that meet their expectations. A skills training and industrialisation agenda might be inadequate to address the employment concerns of this demographic group.

Increase in marginal work for women

Illiterate and semi-literate women have a very low unemployment rate. A possible explanation: they are absorbed in the informal sector that requires low skills and offers low remuneration in sectors, such as services, manufacturing, wholesale trade and construction at low wages.

Close to 20% of urban females work as domestic help, cleaners, vendors, hawkers and salespeople. 43% of urban women were self-employed and the same proportion of women had regular wage salaried jobs, according to NSSO in 2011. Yet, 46% of urban women with regular wages have no social security or employment benefits, while 58% have no written contract for their jobs.

Skill-development programmes, such as vocational training and entrepreneurship development, might be beneficial to some extent for this group of workers and might enable them to move from vulnerable occupations to more secure ones. However, skill training is only one of the measures that will lead to better employability. A number of other factors such as societal and gender norms, education levels, access to credit and so on affect the employment sought by and available to these women.

Why Make-in-India and Skill-India Mission may fall short

India has transitioned to a $2 trillion economy in the past two decades without creating adequate and secure jobs for its large, mostly-unskilled labour force.

The current government is attempting to address this issue through two related sets of interventions. First, by promoting the industrial sector in India through the Make in India campaign and second, through the recently-launched Skill India Mission, which aims to train 400 million workers over the next seven years.

These interventions assume that industrialisation will drive job creation, following the development trajectories of the East Asian economies.

An examination of the numbers presented above allows us to question this assumption and add an additional set of priorities for India’s employment agenda. In their current form, these policies are not sufficiently cognisant of the changing composition of the work force, particularly in relation to women who comprise half of India’s potential work force.

An explicit focus on the changing nature of women’s work is essential to ensure the sustainability and inclusiveness of India’s growth.

This article has been republished from IndiaSpend.com.