The magazine’s cover story begs a question on who we call a terrorist and what we deem an act of terror.

What is terrorism? That is perhaps not the easiest question to answer but has become an increasingly important one to address. While the courts have a fixed definition based on which they adjudge, terrorism acquires a fairly broad meaning in mainstream discourse.

Who you call a terrorist, then, often reflects what you consider a crime grave and senseless enough to be labelled an act of terror. For some, Maoists ambushing paramilitary forces in Dantewada is an act of terror, for others it could mean politically-motivated killings in response to a prime minister’s assassination. (In the context of the Tarun Tejpal case, one Bharatiya Janata Party leader stated that rape is a form of terrorism.)

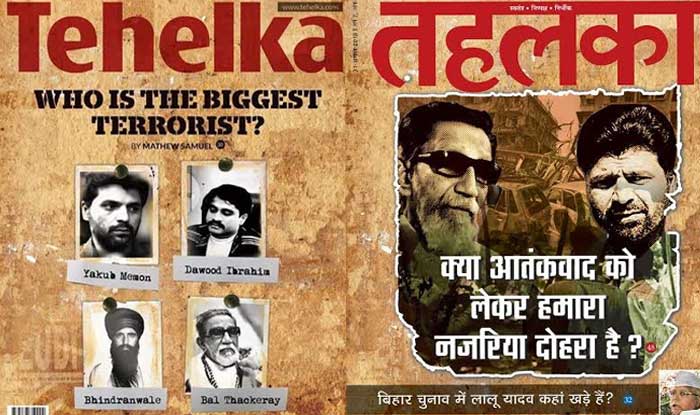

It is precisely this predicament that this month’s issue of Tehelka magazine seeks to address with its cover story: Who is the biggest terrorist of them all?

The author of the story and Tehelka Managing Editor Mathew Samuel writes: “If terrorism were to be defined as a belief system that legitimises the use of all possible means to terrorise people in order to further a political cause, how are the anti-Muslim massacres — for instance, the Bombay riots — any less “terroristic” than the bomb blasts carried out by underground Islamic groups?”

Mathew cites heavily from the findings of the Sri Krishna Commission.

He says: “The killing of Yakub forces us to revisit the crimes of the man who was key to some of the most brutal acts of terror in this country. Why is Thackeray, the cartoonist turned- rabble-rouser, not counted among the most dreaded of “terrorists” and as one of those who contributed the most to killing the idea of India?”

The Maharashtra Navnirman Sena lodged a complaint against the magazine for the piece and its audacity to talk about Yakub Memon and Bal Thackeray in the same breath while stating that the Bombay riots were as much an act of terror as the 1993 bomb blasts.

To be sure, Samuel’s is among the few voices that questioned the Indian state’s hypocrisy in dealing with violence and what it deems an act of terror. Indeed the media across the world has different standards while labelling acts of violence either by the state, an organised terrorist group or a lone wolf.

The immediate example that comes to mind is the United States’ war on terror in response to the 9/11 strikes that led to 1.3 million civilian deaths in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. But in popular and media discourse, rarely would anyone equate the United States to a rogue state or accuse it of state-sponsored terrorism. Earlier this year, though, Nicolas Maduro, the President of Venezuela, declared a ban George W Bush from entering country, labelling him a terrorist.

The Madrid train bombing in 2004 and the London bombings in 2005 by Islamist groups were widely referred to as terrorist attacks. While the Oslo attack in 2011 was mostly called a slaughter, a shooting or a massacre. This despite the fact that it was carried out by a Christian extremist Anders Behring Breivik, who used bombs to denounce European liberalism.

There was also the time when TIME magazine headlined a report on the Soviet Union shooting down a Korean passenger plane as: “Shooting to Kill – The Soviets Destroy An Airliner”. Contrast this to the headline it used when an American naval warship shot down an Iranian passenger jet accidently: “Iran’s Jetliner. A Clash Turns To Tragedy”.

Coming back to the question of how we (and the media) label an act of violence, prominent sections of the media in the US stated that the recent Charleston church killings should be reported on as an act of terrorism, and not as a “hate crime”.

Dara Lind wrote in Vox: “Labeling the Charleston church shooting terrorism is a way to recognize that black lives matter.”

In the Daily Beast, Dean Obeidallah wrote: “Bottom line is that if we want to save American lives, we need to address all forms of terrorism. We need to dedicate government resources to counter right wing terror plots as well as those connected to ISIS or Al Qaeda.”

That in essence seems to be the point that Samuel makes in the Tehelka piece. That people who lose their lives in riots (which often have the tacit approval of the state) matter as much and are as deserving of justice as those who lose their lives to terror attacks.

That the nation’s “collective conscience” must seek retribution not just from the masterminds that arm young people with bombs and AK47s to carry out terror strikes, but also from those who send out armies of men with swords and kerosene to kill with impunity.

In the big picture, labelling the late Bal Thackeray a terrorist may not help, just like hanging Yakub Memon would not. But can we at the very least start recognising riots as an act of terror?

This article was republished from the Newslaundry.com.